Dionisio González: “I am sitting here in a little place inside a beautiful fjord and thinking about the beastly theory of types.” Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951), in Norway in 1914, sketched and planned the construction of a wooden house on the steep shore of Lake Eidsvatnet in Skjolden, beside the Sognefjord, about a mile away from the village. In that small space, on a slope, Wittgenstein had found the tranquillity he needed to work ascetically, like a hermit, on his studies of logic. After deciding on the location in which to “ensconce” himself, in order to disappear and concentrate on the work of thinking and contemplation, he built a house and a small jetty. To access it, one had to cross the lake by boat or walk over the ice during the winter months. It was built on a stone platform - typical of local architecture - and in wood, with horizontal planks, a slate roof and rooms at different heights; one of its façades was asymmetrical.

World War I delayed Wittgenstein’s return to Norway until 1921, and his last visit to Skjolden took place in the September holiday of 1950, when he was convalescing, and suffering from prostate cancer. There, with his friend Ben Richards, he studied Frege’s Foundations of Arithmetic. He had intended to come back again, and purchased a ticket on a steamship that was due to set offfrom Newcastle to Bergen in December, but by then he was too weak to embark on the journey. As Heidegger said, we are only capable of inhabiting on the basis of rootlessness.

This way of building from withdrawal with the purpose of study and observation is the manner in which Wittgenstein sought the feeling of flight from the world, deviation towards somewhere – another way, nowhere/nobody. It is an apparent construct, an unfenced extension in the midst of unlimited space and analgesic cold. The flight is crystallized through the harsh winter, through the snowy scenery and the clear, biting air. The literal or symbolic journey undertaken frequently runs between mountain ranges and among fronts of admonitory clouds with barely any breaks in them, like ripped curtains above the rocky peaks. Only winter, the season indicated by the north wind, the white, virgin edge of the north, where the snow blankets the earth and the animals go into hibernation, shows the runaway which slope can be used to cross the wintry, inflamed solitude.

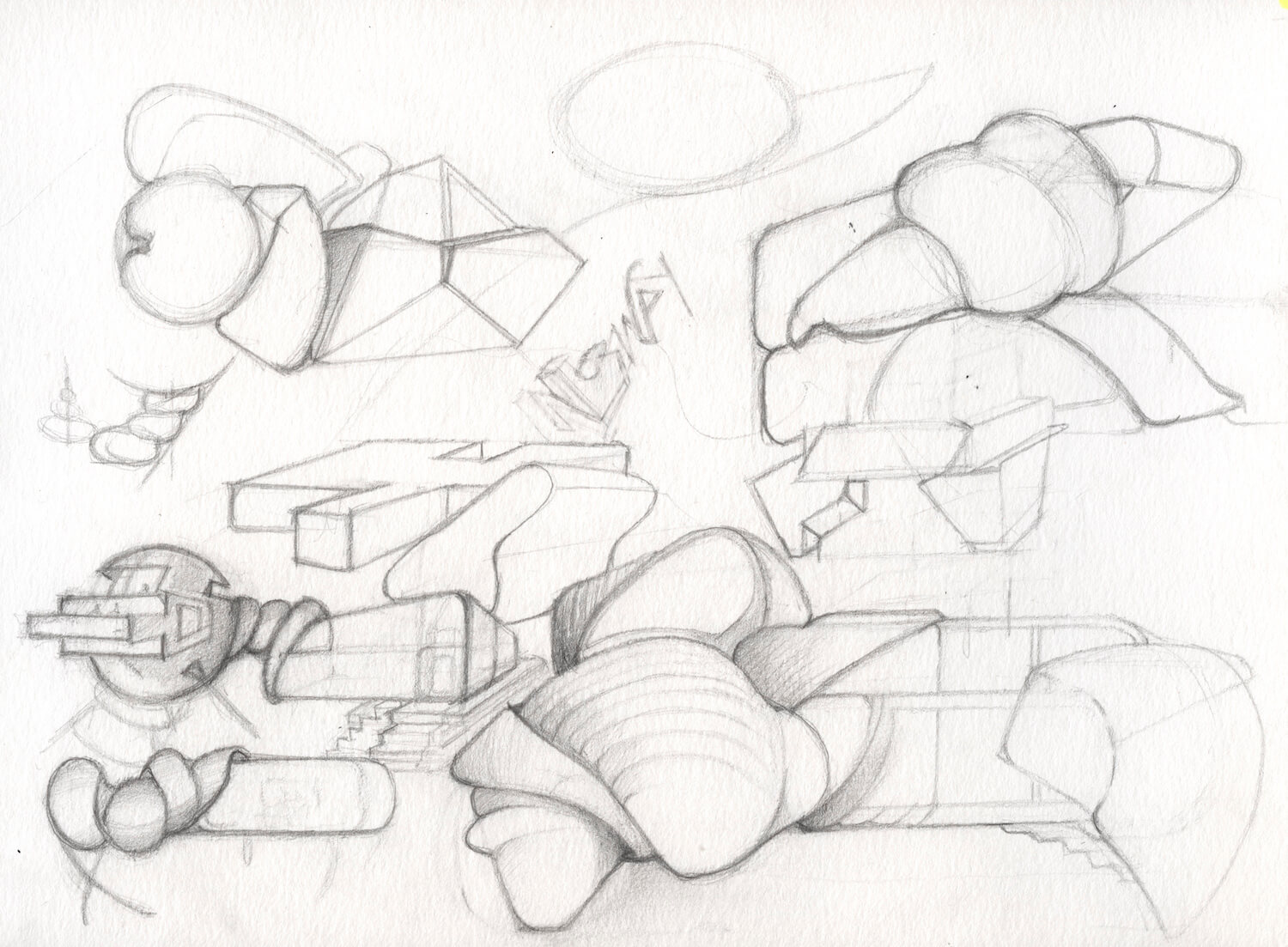

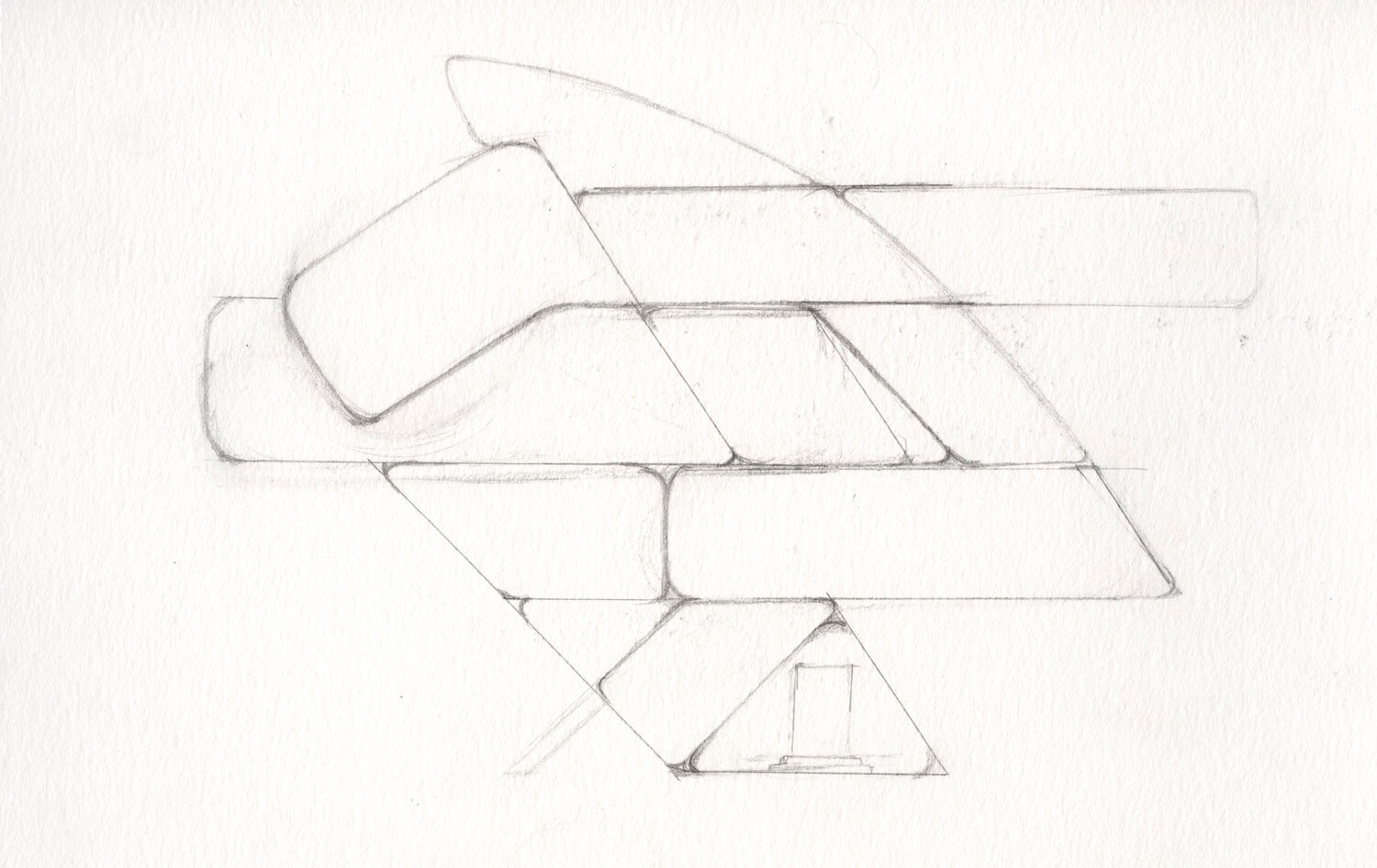

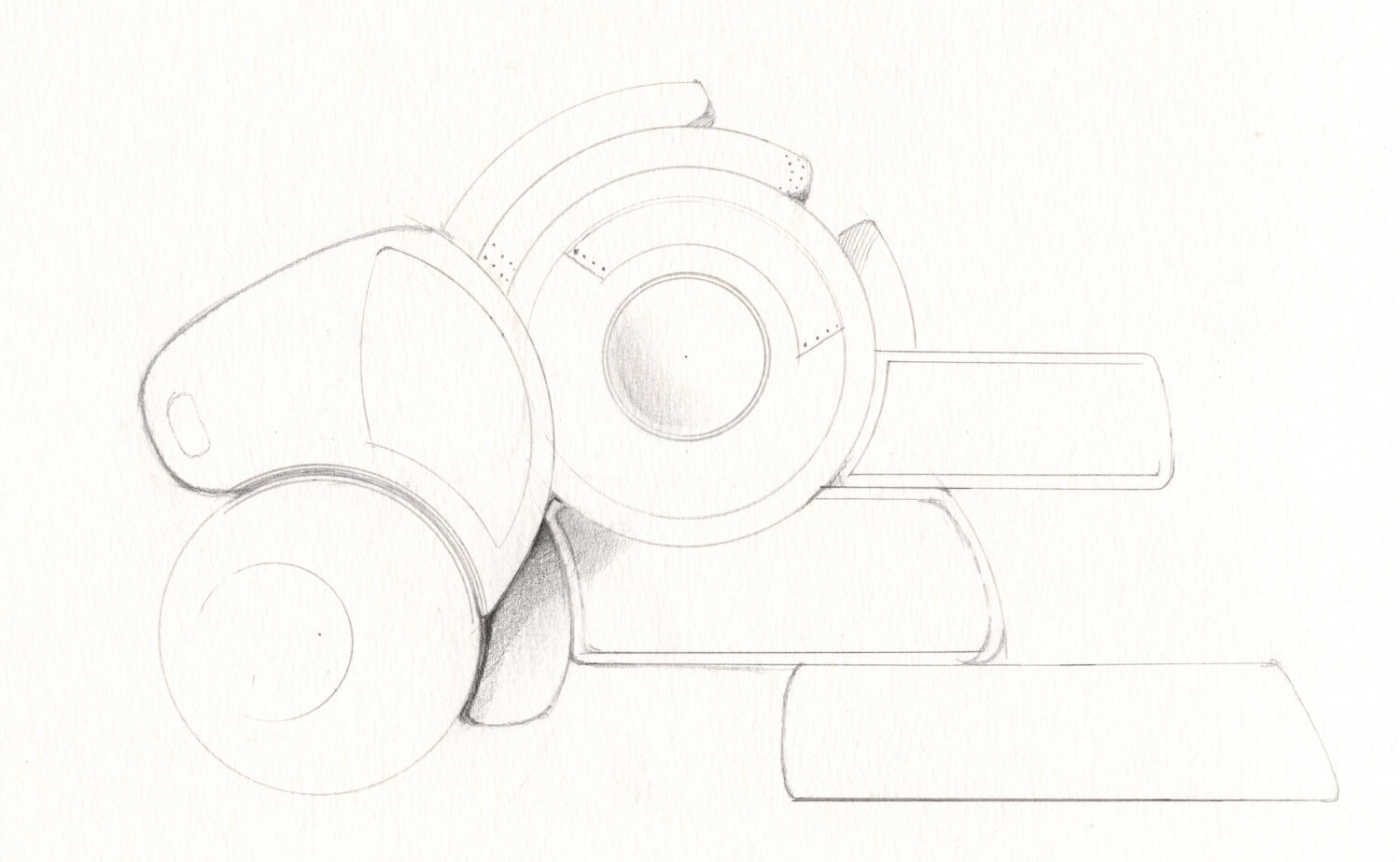

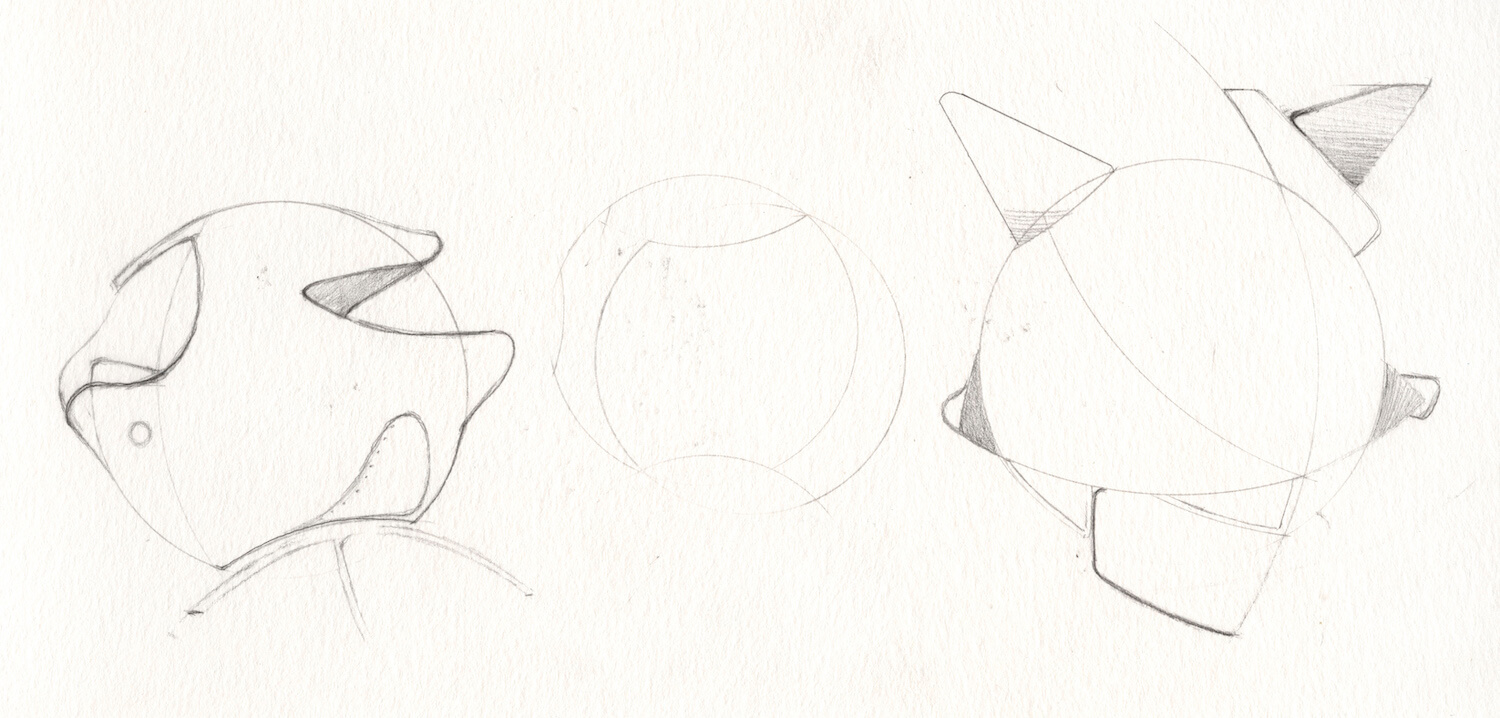

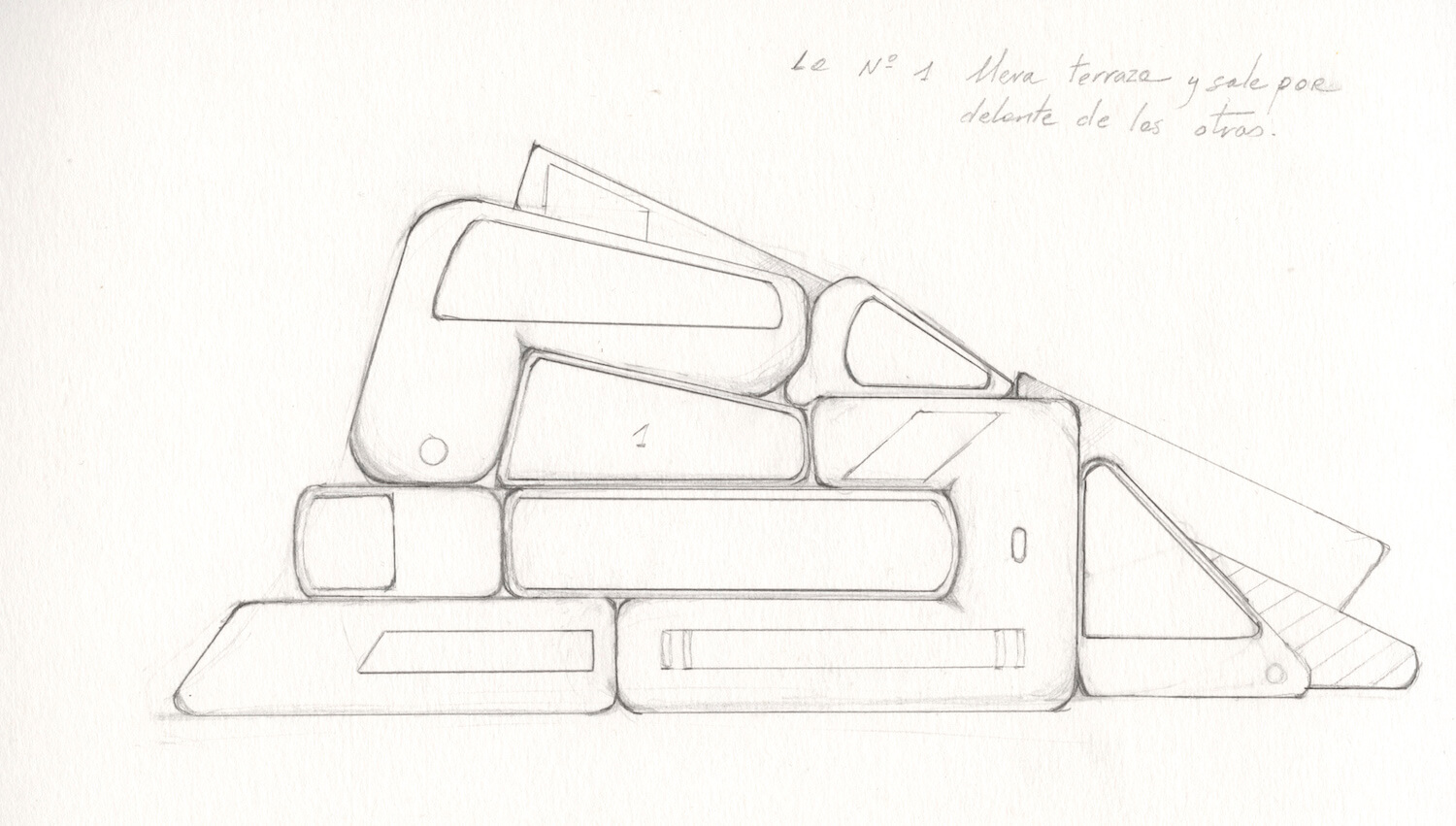

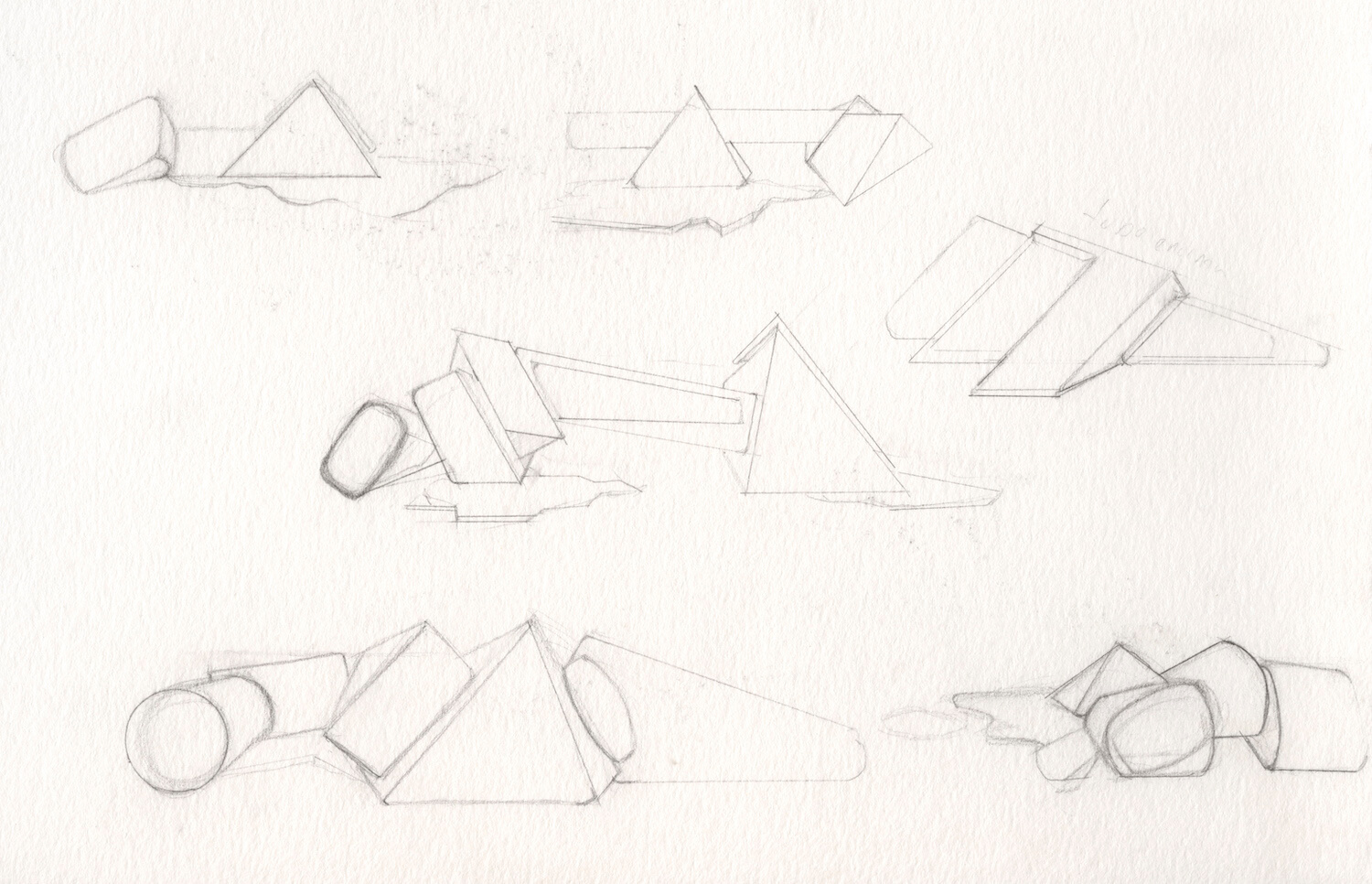

This series, Wittgenstein ́s Cabin, analyses that early structural plan of architecture, the cabin. Today, still, unaffected, genuine concepts operate on wooden houses, relating them to late romantic objects which project debates surrounding singularity and frankness. Surrounding unornamented, essential states where one lives in severe, spartan order, in more direct contact with the natural environment and in relation to subsistence and time for reflection. Wood constructions and wooden interiors in themselves act as insulation, unlike what occurs withother materials. The possibility of increasing these values with greater ease than in traditional systems, and with a smaller loss of useful surface area, means wood is widely used as a building material in countries with extreme climates. The acoustic properties of wooden houses are excellent, as wood absorbs any waves it receives. The wooden house is a silent house. The walls of Heidegger’s cabin in the Black Forest were (are) cladded in wood shingles. Heidegger always intimated that philosophy transmuted the landscape into words through it, almost without intermediaries, as the sole shift and process between euthymia and space.

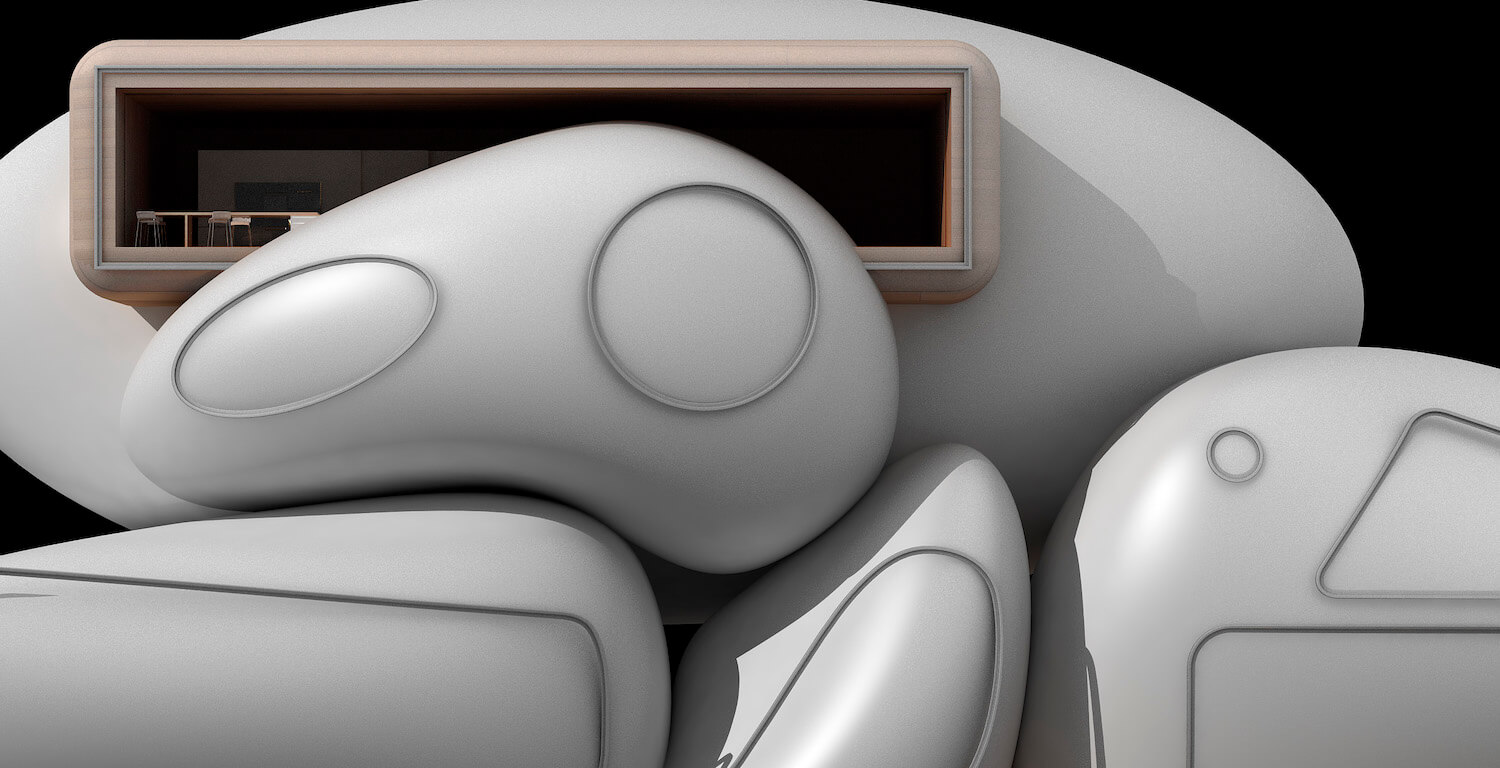

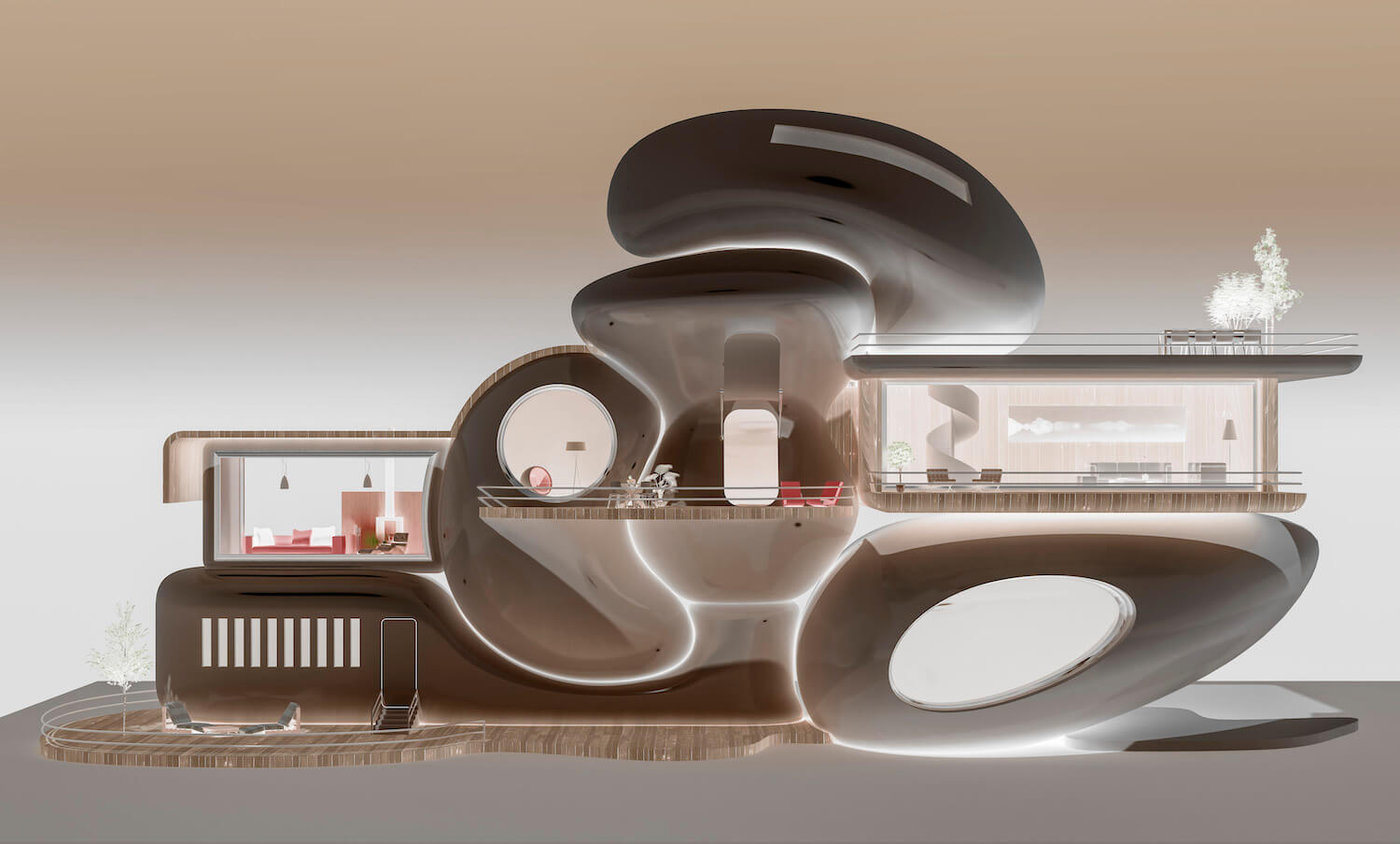

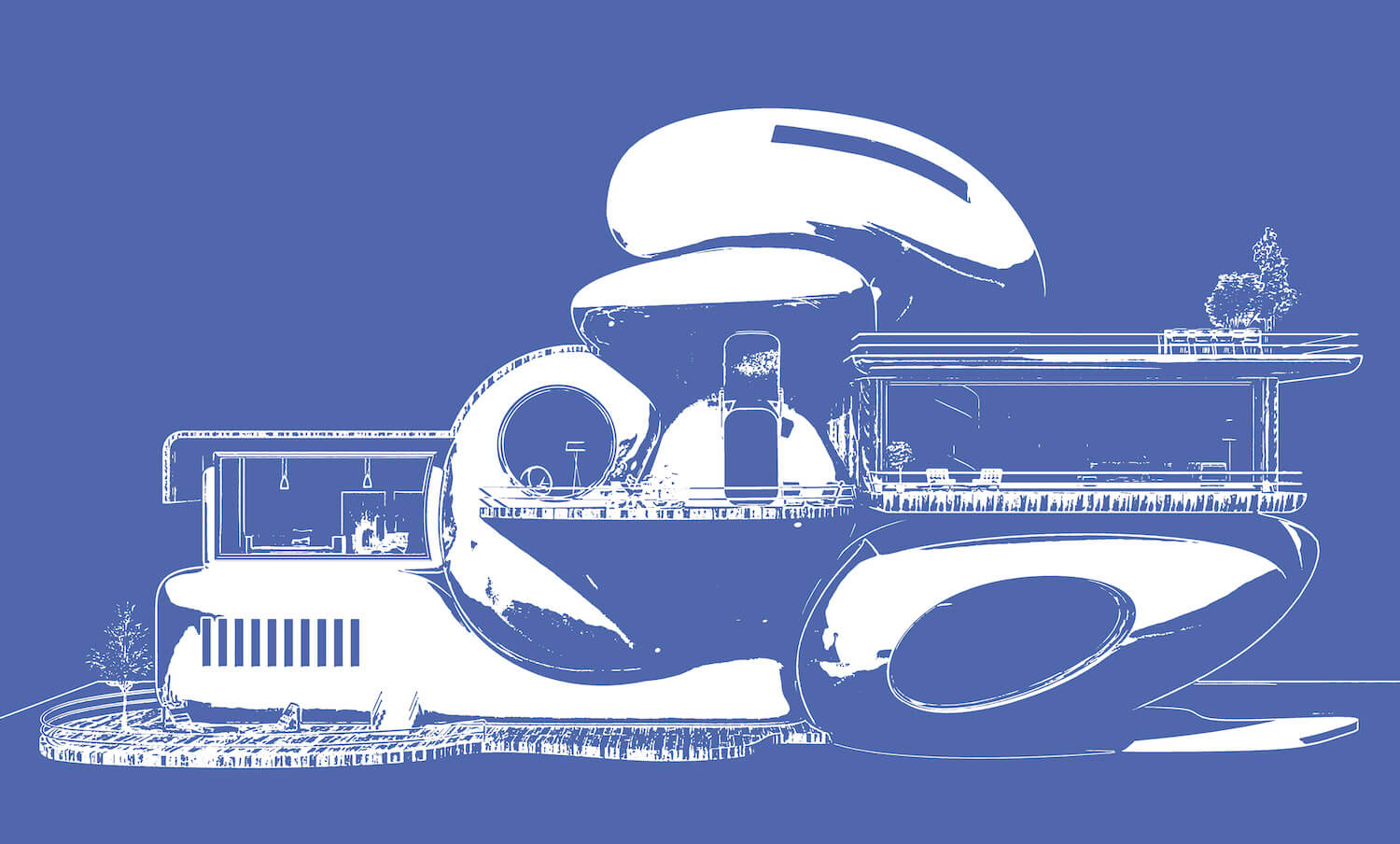

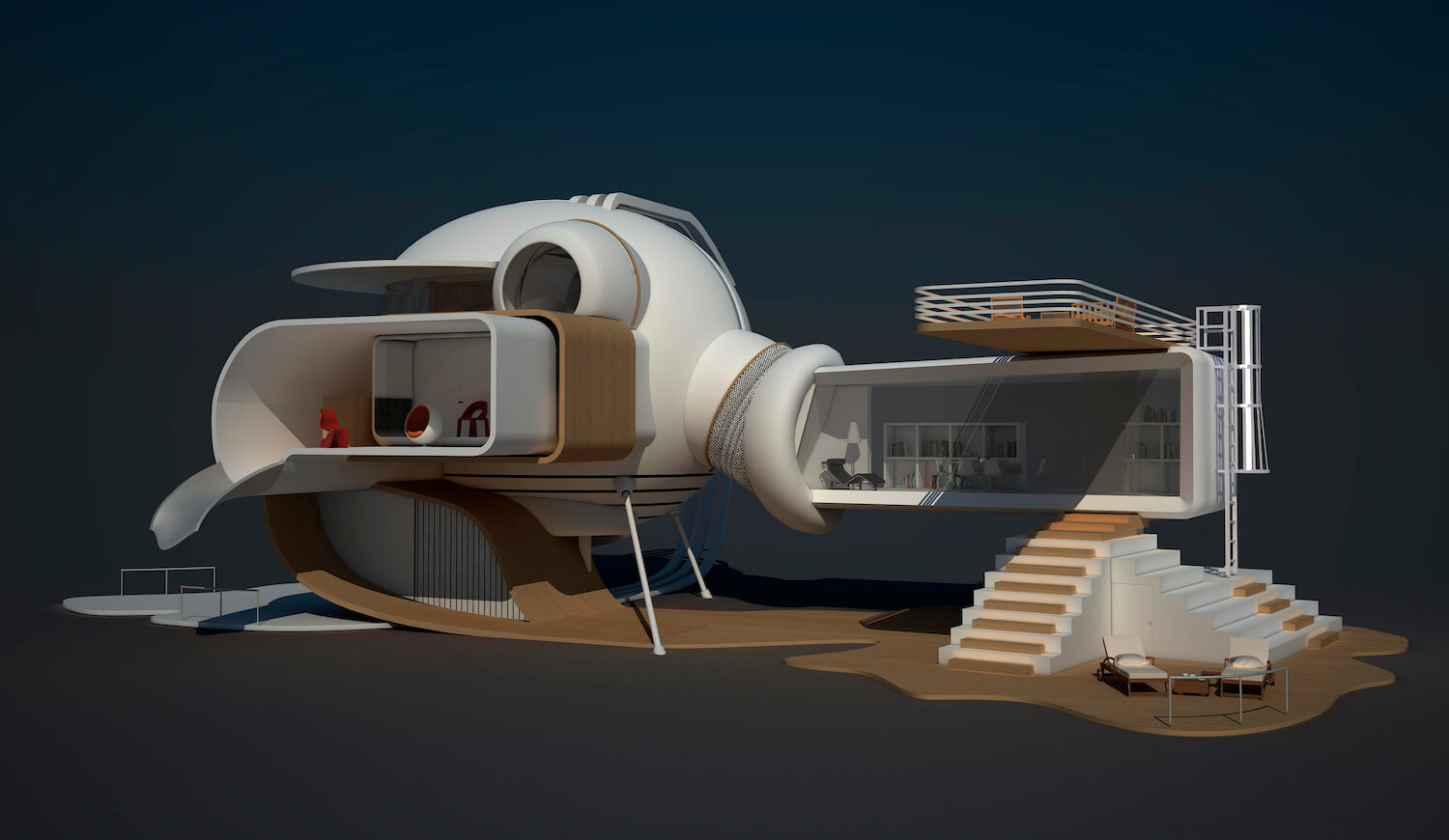

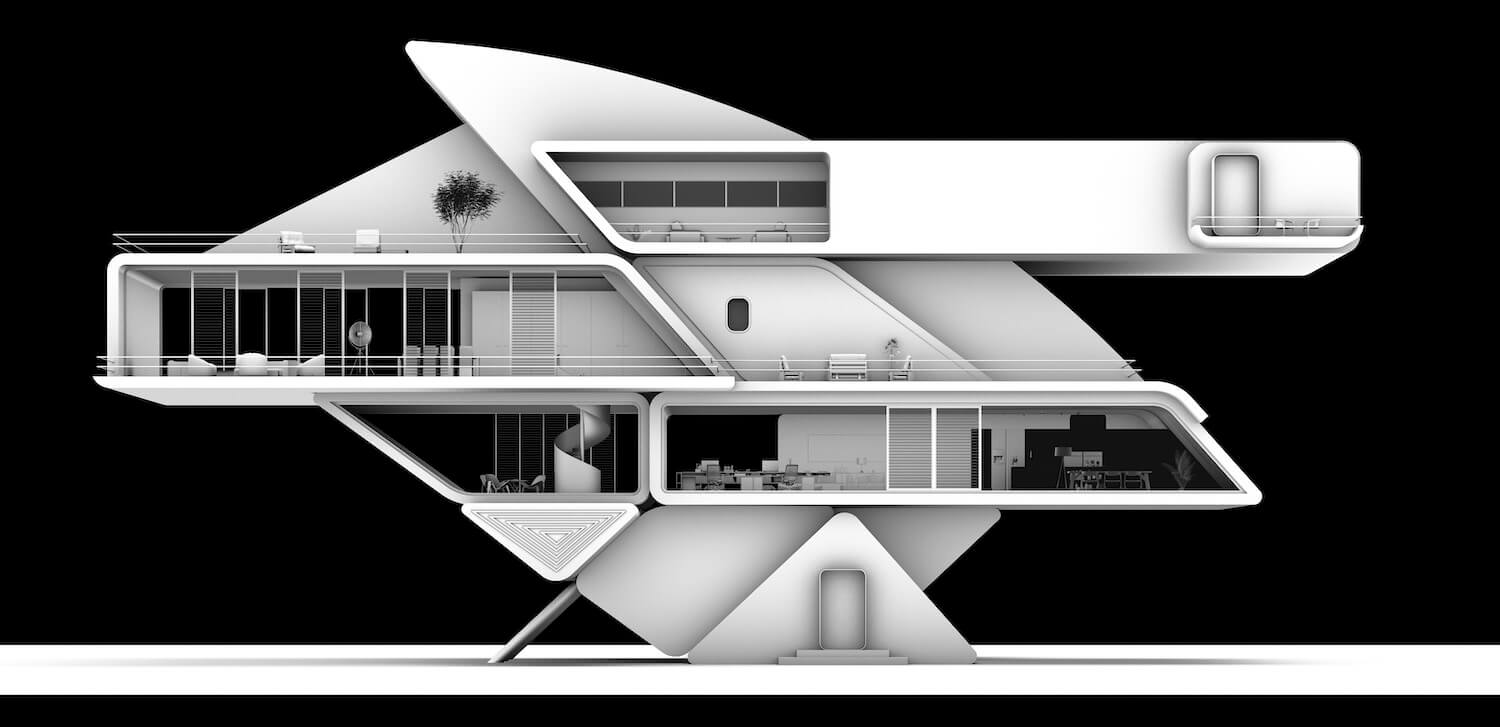

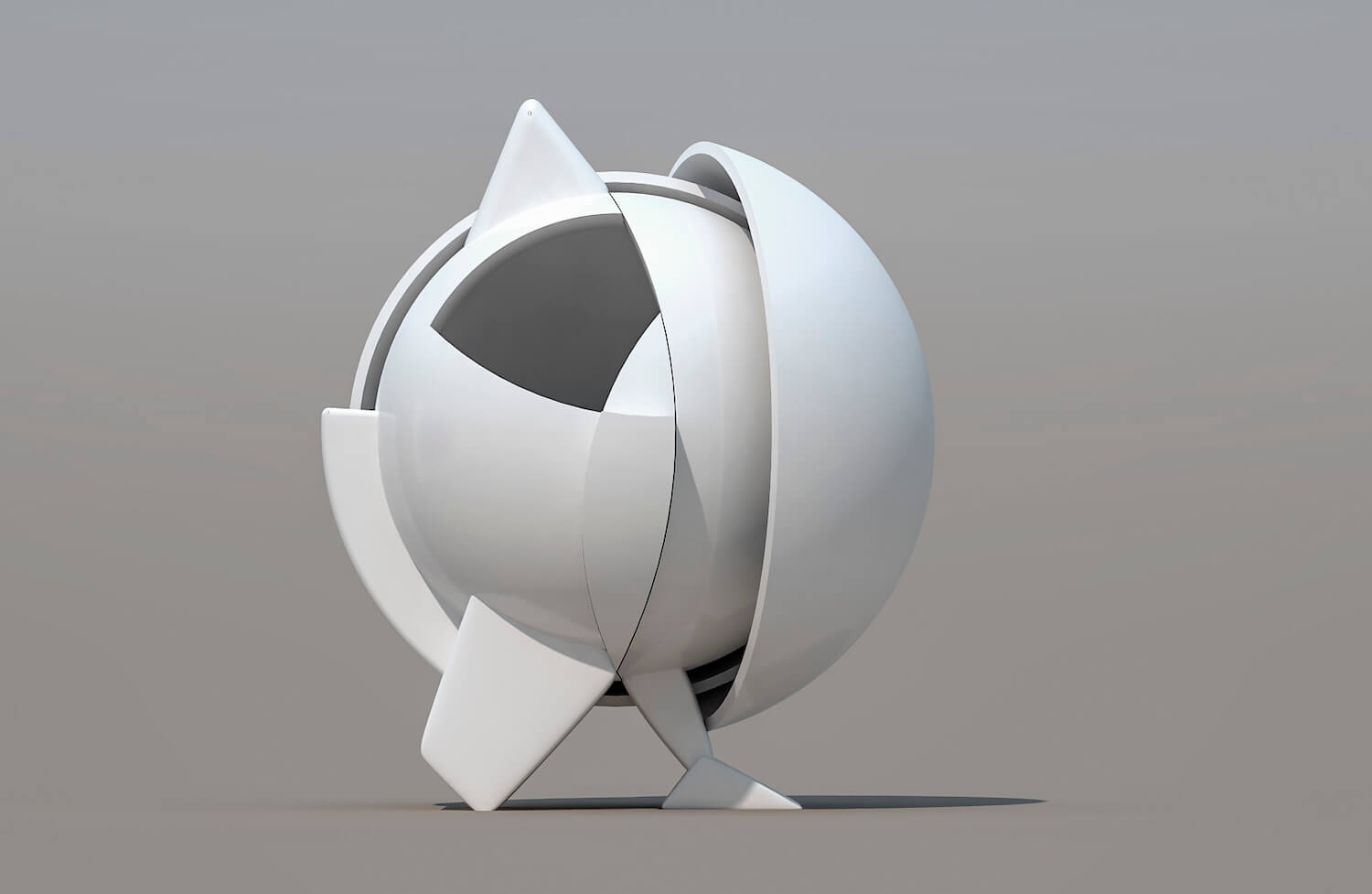

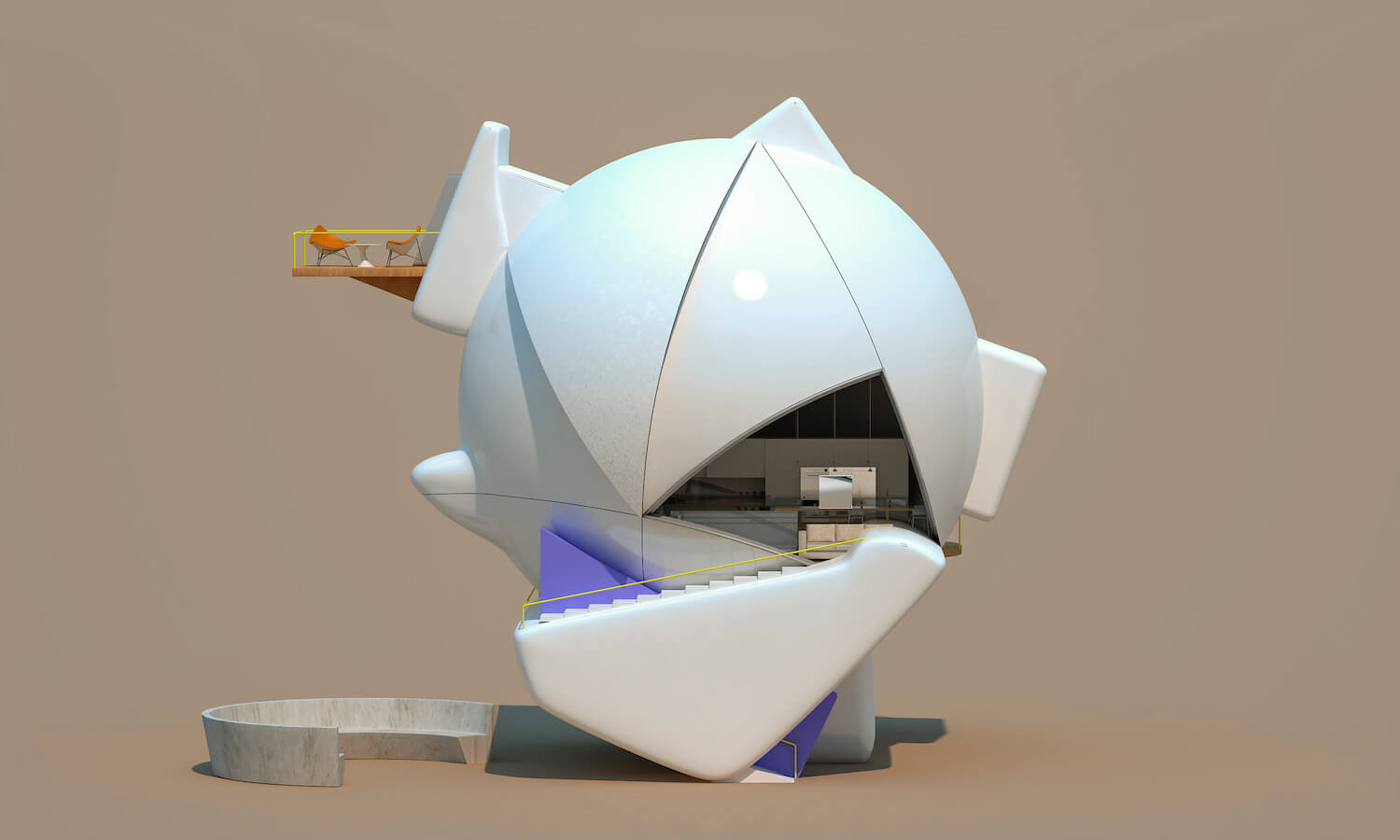

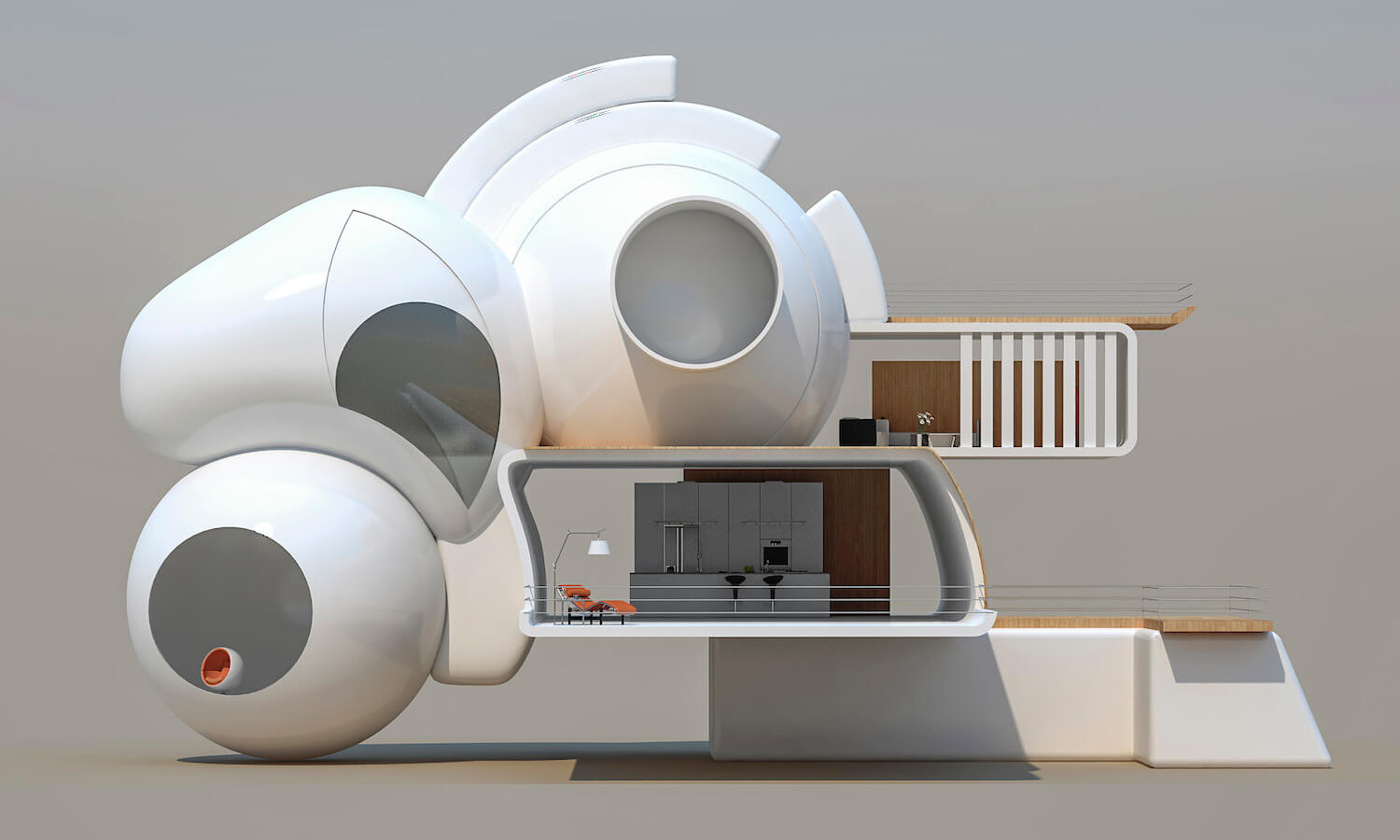

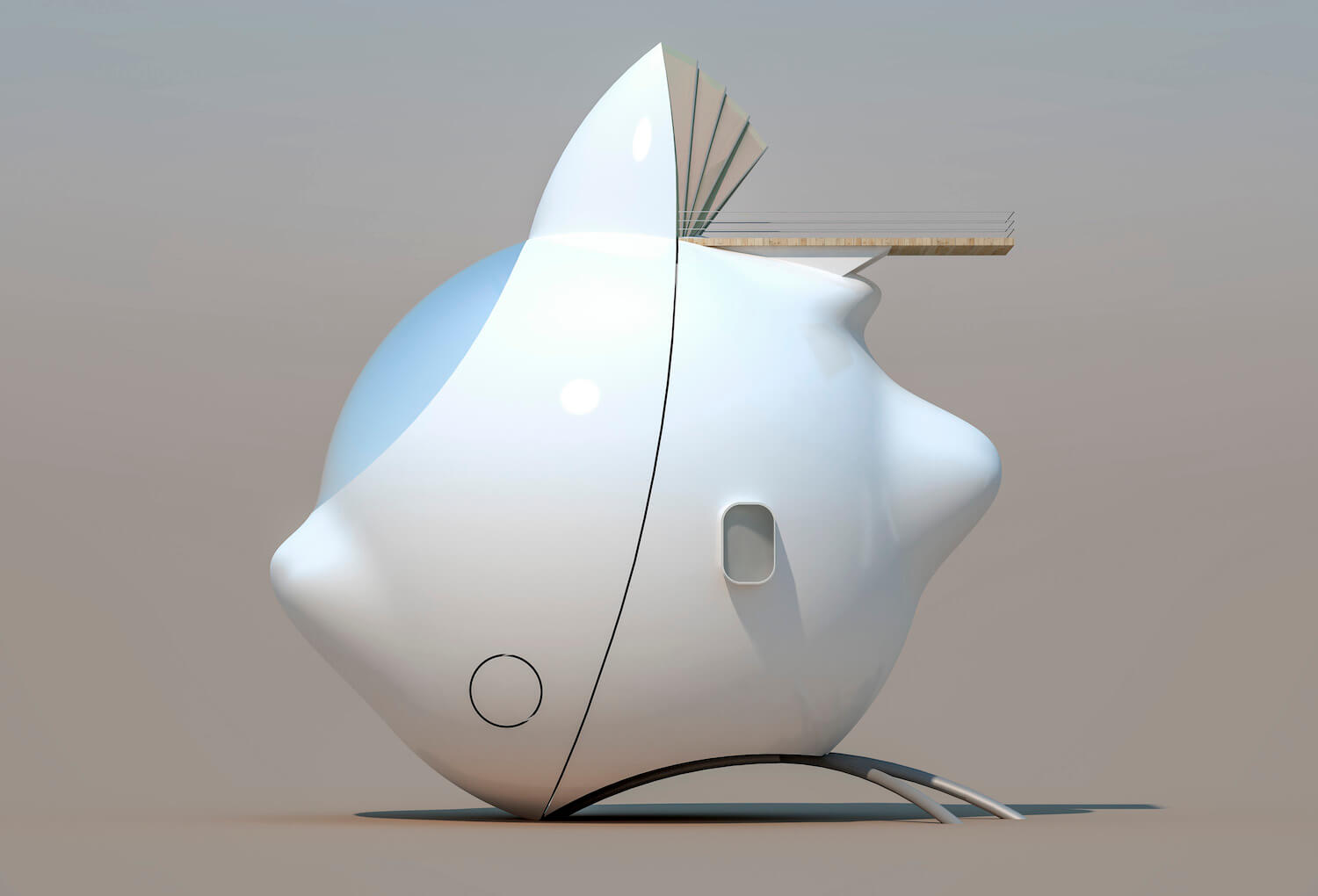

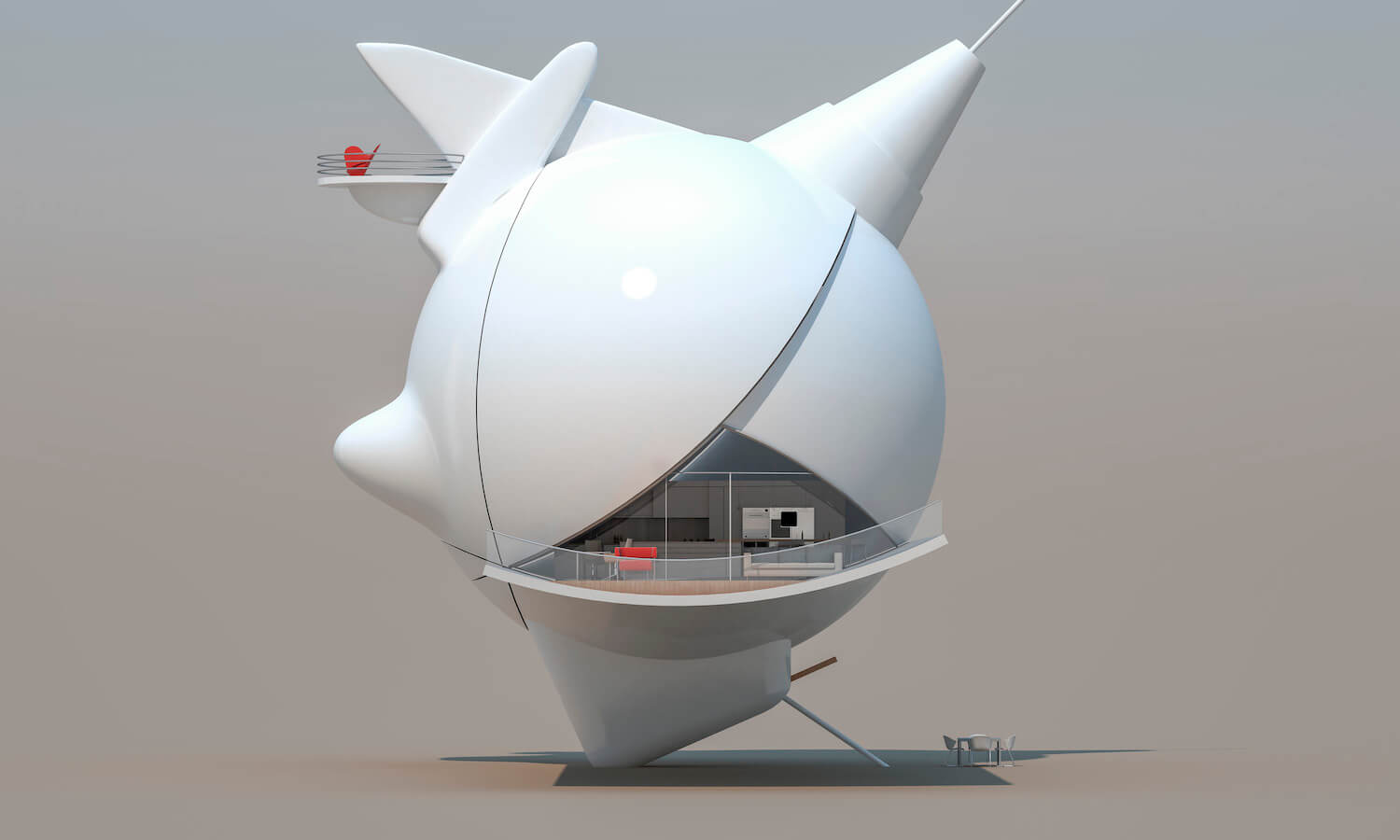

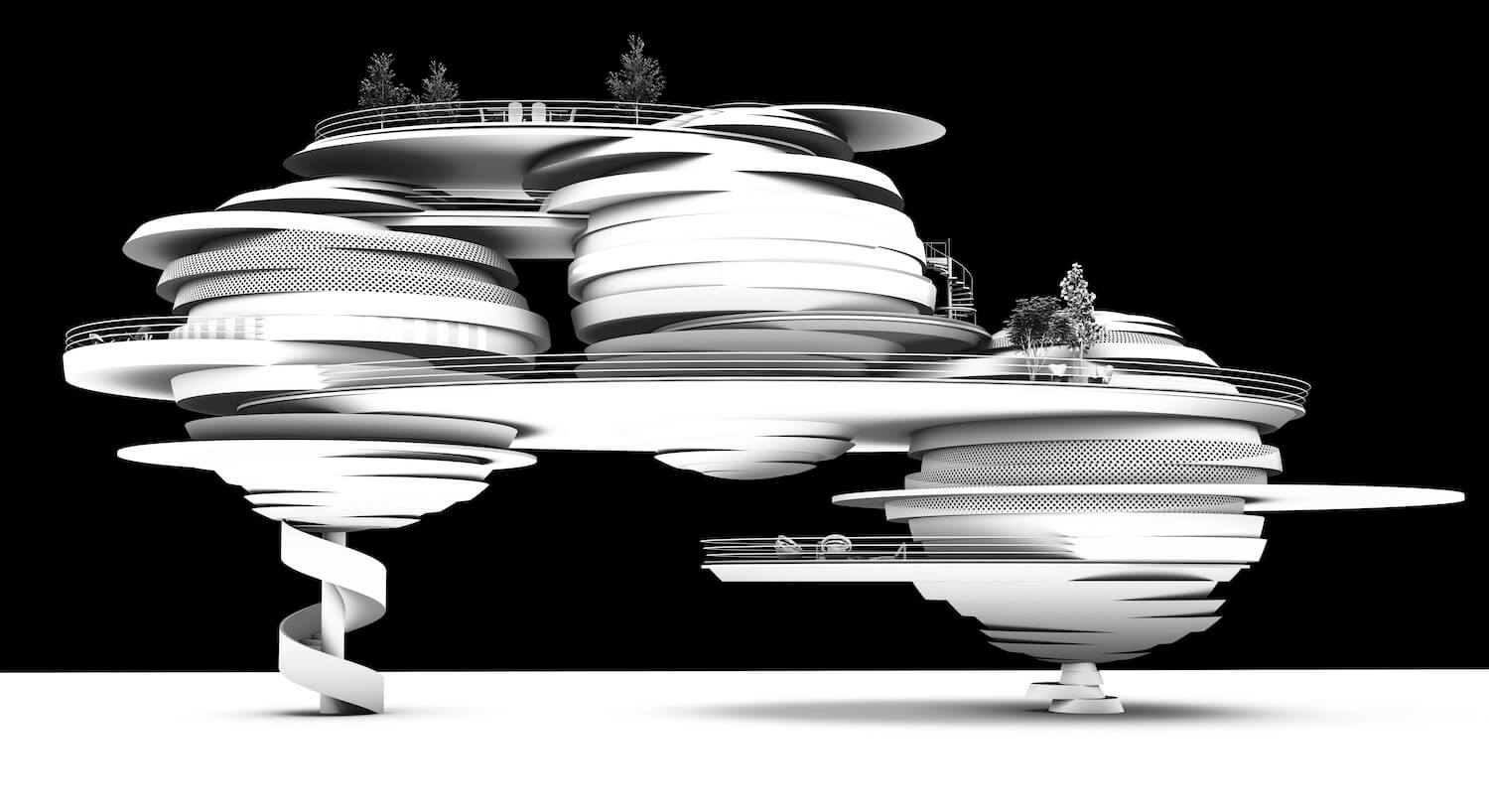

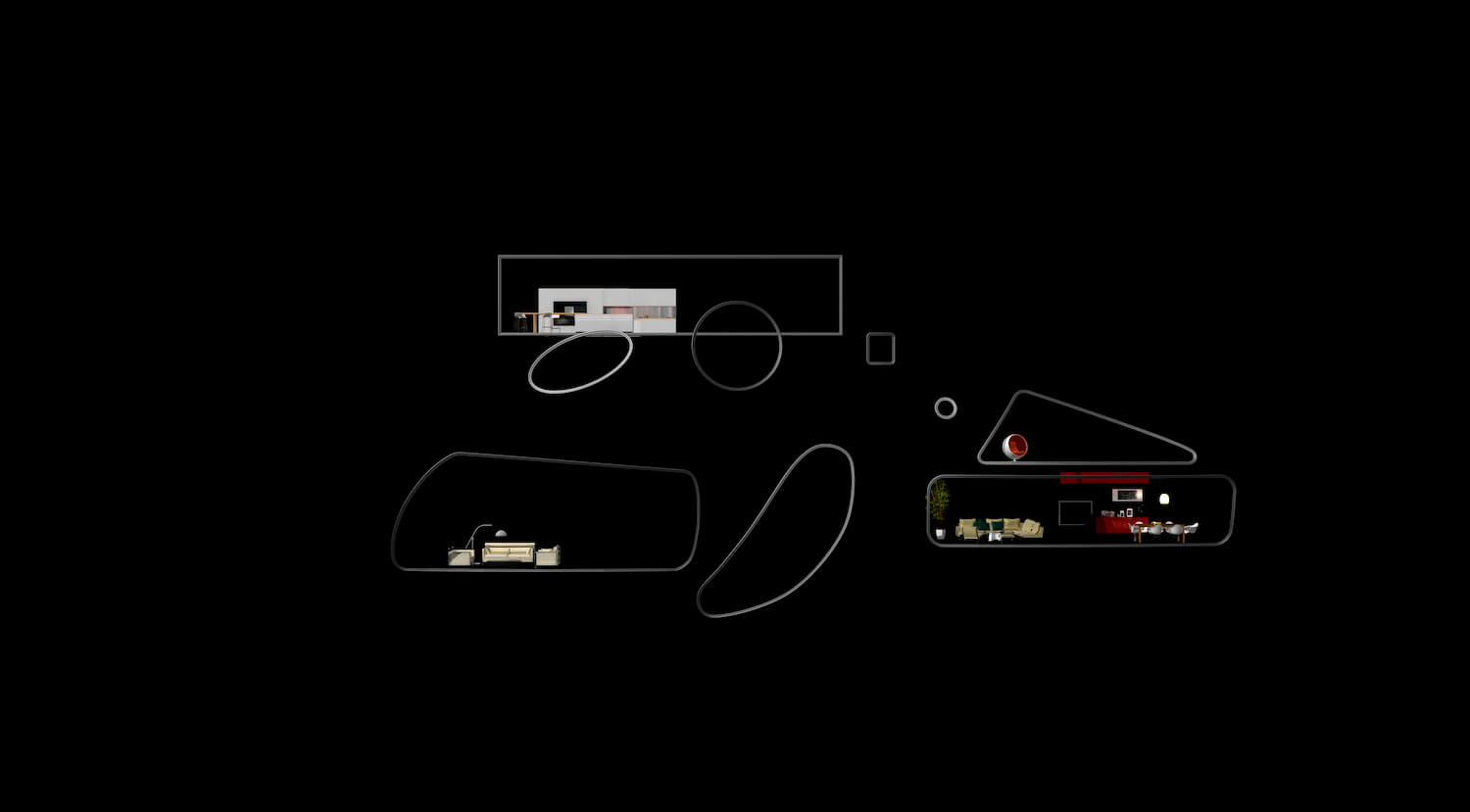

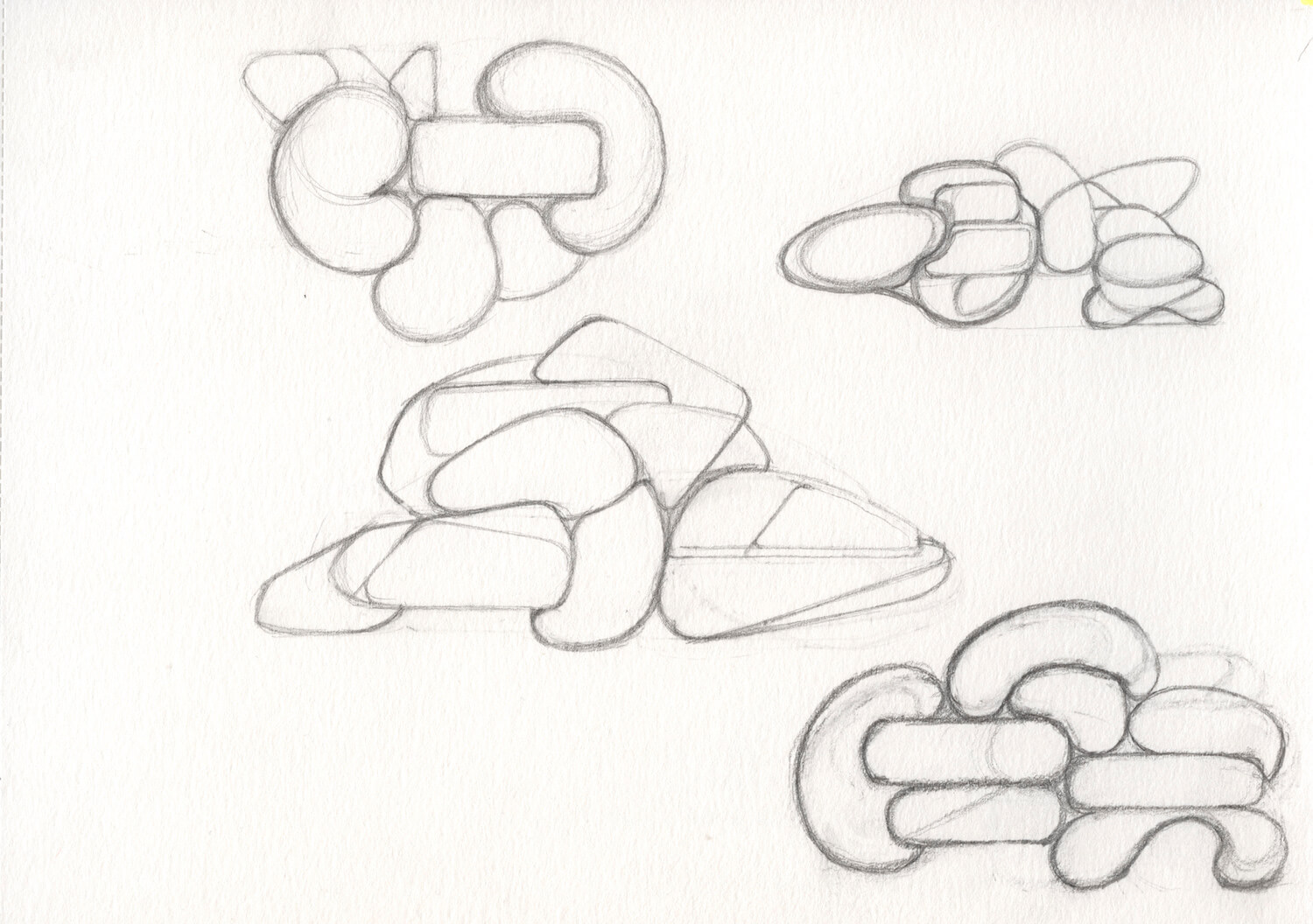

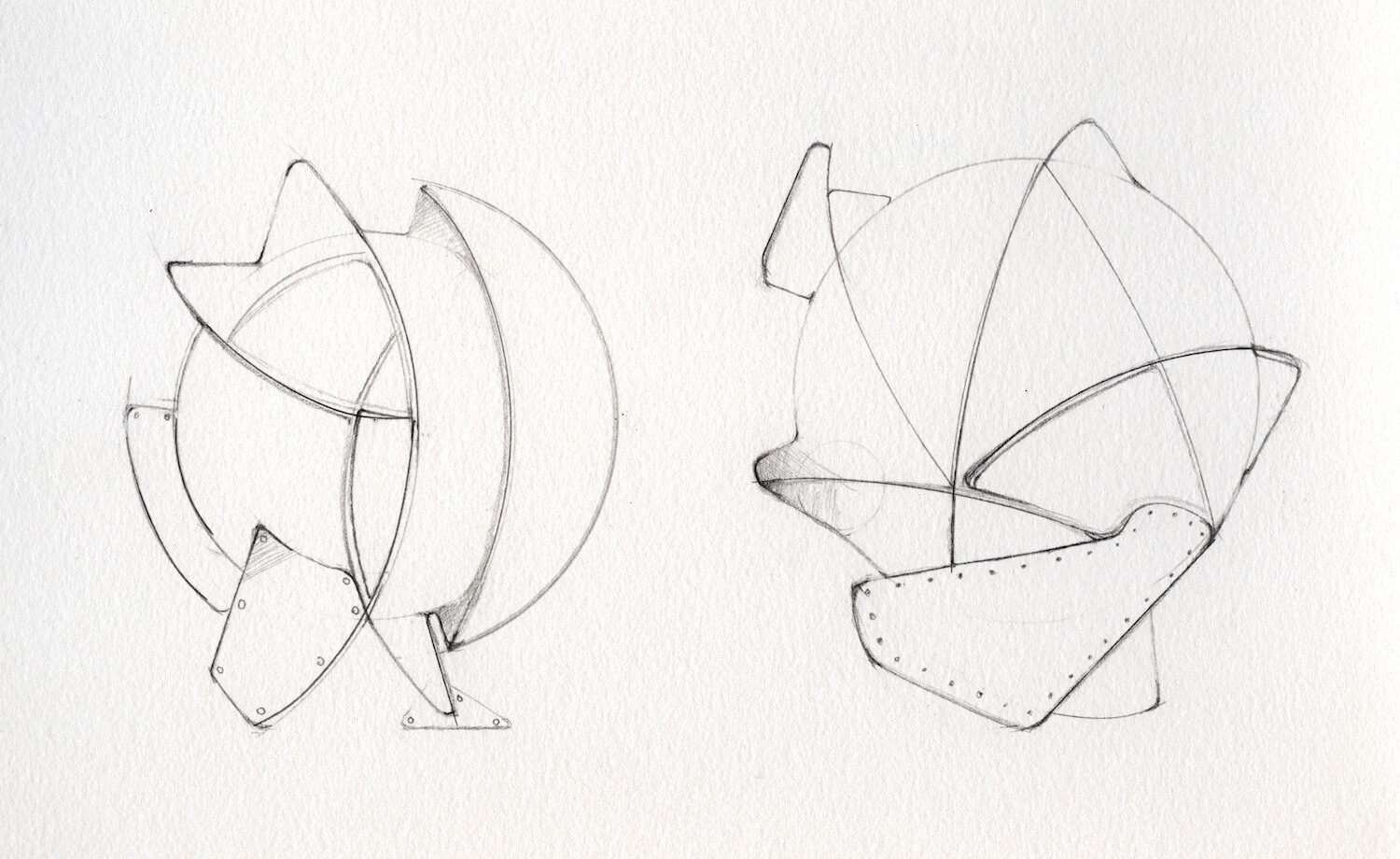

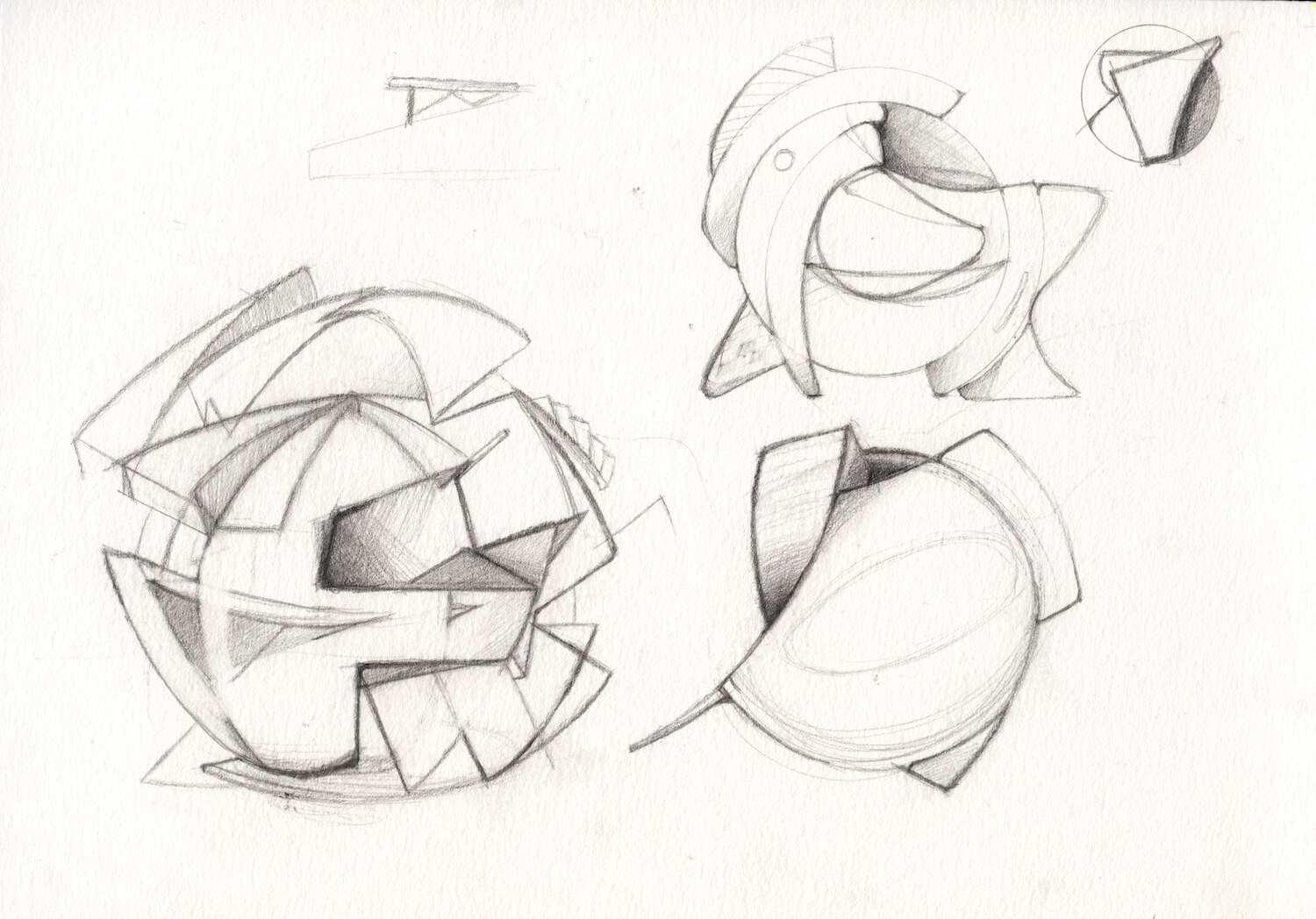

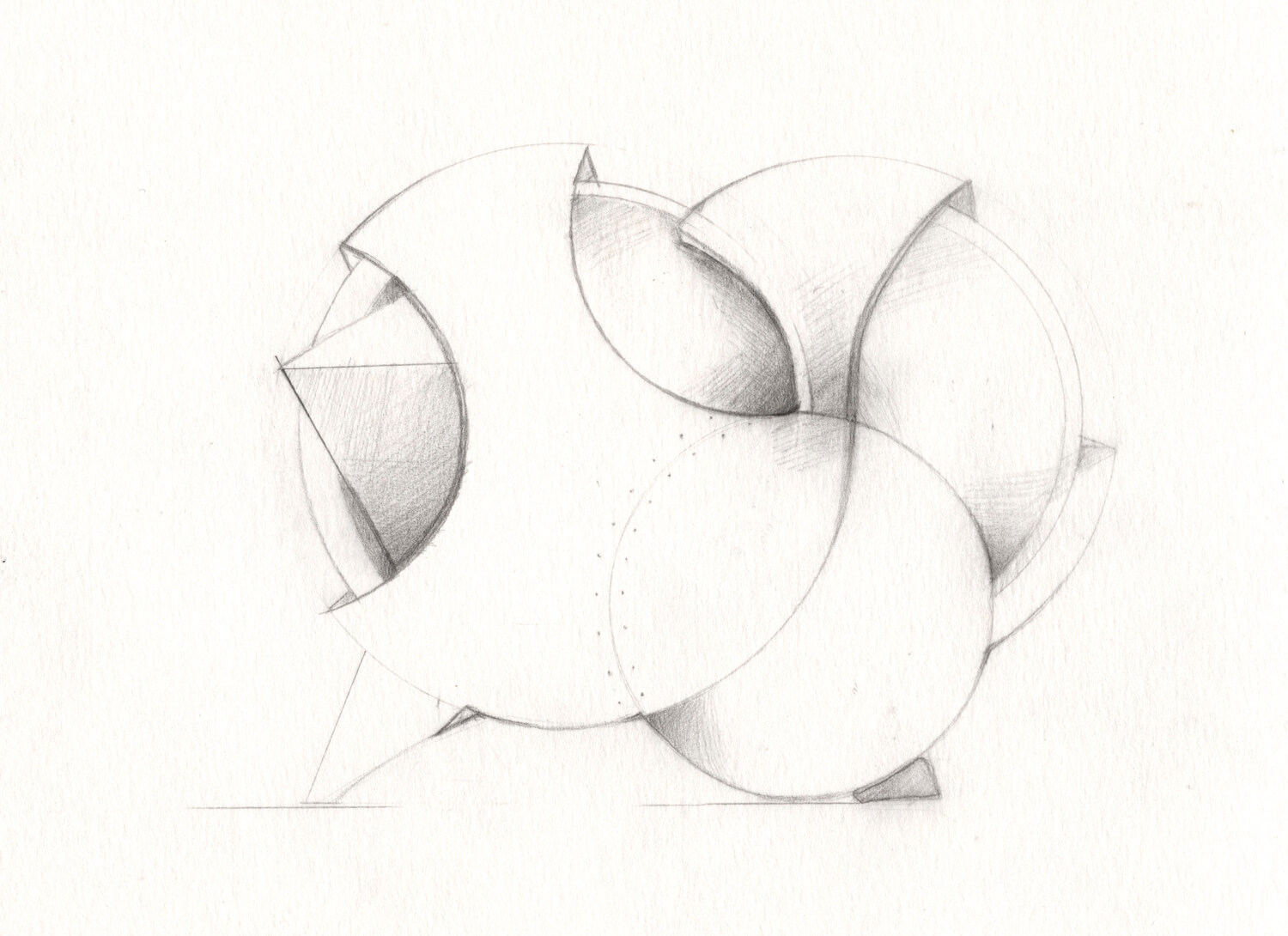

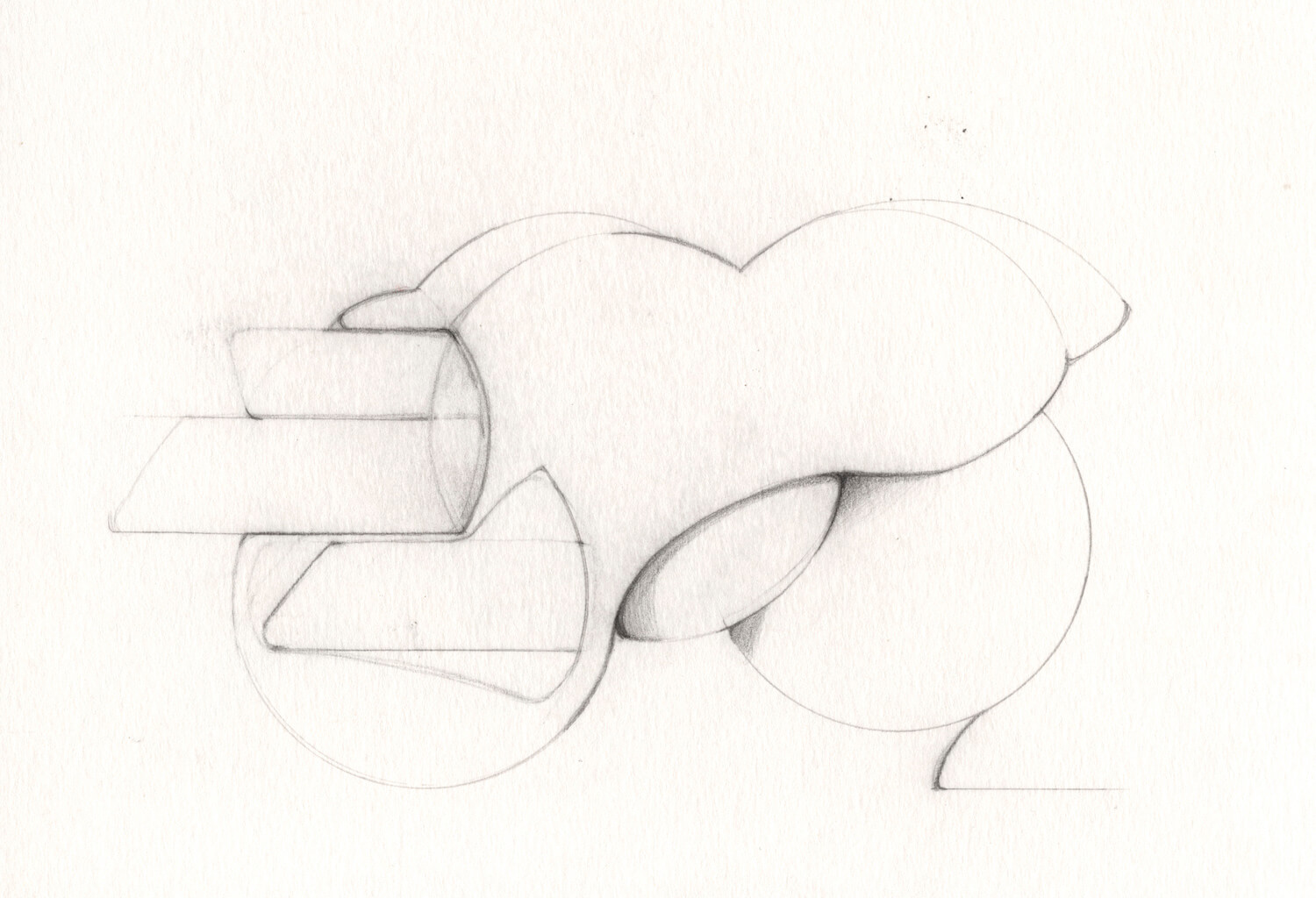

But there is something revealing and emphatic in Wittgenstein’s Norwegian cabin, and that is the confrontation, the frontality with the fjord, with the water lodged behind the action of the glaciers. Wittgenstein worked on his studies of logic on a boat his friend David Pinsent sailed in the Sognefjord. This fact, this “event” of the research, the learning and memorizing on a small aquatic means of transport, which serves as a writing desk, led me to consider the relationship of architecture with water, and of philosophy as an “amphibian” endeavour. How would Wittgenstein frame that organic building, that architectonic construction in a liquid medium with the present media? What would contemporary cabins be like in diffracting settings of propagating waves, such as the Norwegian fjords? A setting, not in the sense of fascinating backdrop or proscenium, but as a function and medium in itself. With their ductility and contractility, depending on the months of the year. With the seasonal changes of liquid to solid. “Im Anfang war die Tat” (“In the beginning was the deed”), Goethe’s verse in Faust, which Wittgenstein quoted with approval, was perhaps the rubric, the statement of all of Wittgenstein’s late philosophy. And perhaps, too, the principle from which to face the challenge of the construction of an aquatic retreat. Ultimately the Austrian philosopher would say, Am I not getting closer and closer to saying that in the end logic cannot be described? You must look at the practice of language, then you will see it.

That you will see it is the function of this series. That recreating a world of possibilities, complex but anchored in logic, which can be conceived as real. Prototypes for thought, amphibious dwellings for reflection in their double conception. Because all of these living quarters are reflections of the world (for Wittgenstein the world is the limits of language) and in turn, they are reflected on the mirror of the waters which are, in another measure of space, reverie but always flight, retreat, metamorphosis.

About Dionisio González

Dionisio González Lives and works in Seville. Spain Visual artist of recognized international prestige whose work proactively explores the habitat problems faced by vernacular and irregular architecture and the great failed construction utopias of the second postwar period. In short, those architectures exposed to their collapse and blurring. It has multiple awards like: Pilar Juncosa and Sotheby´s Award. Fundació Pilar i Joan Miró. Best European Photographer Arendt Award. D´Achtall Observatory Photography Award. National Engraving Award. Off PhotoEspaña Festival Award. Patronage of the María Cristina Masaveu Peterson Foundation. Leonardo Grant from BBVA.His work has been exhibited in the most recognized institutions and museums in the world such as: Museum of Contemporary Art. Cleveland. Museum of Contemporary Art of Bourdeaux. (MNCARS). Museo Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. Madrid. Centre Pompidu-Metz. Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago. Museo de Arte Moderno de Bogotá (MAMBO). Folkwang Museum, Essen. Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP), Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCCA), Toronto. Museum of Contemporary Art (KIASMA), Helsinki. Kunstverein of Heilderberg. Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology. MAAT. Lisboa, (MARTA) Hedford Museum. Alemania. etc.

Likewise, his artistic work has been seen in different Art Biennials such as: The 54 Bienalle di Arte di Venezia, Italia. X and XVII Bienalle di Architectura di Venezia, Italia. Biacs, Bienal Internacional de Arte Contemporáneo de Sevilla, España. Busan Biennale, Busan. Corea del Sur. Biennale de Miami, Miami. E.E.U.U. Bienal de le Havre. Francia. Kwang Ju Biennale Art Fair. Corea del Sur. Biennial of Architecture and Urbanism of Shenzhen, Shenzhen .China. XIV Bienal de Arquitectura y Urbanismo. Santander. España.etc

Some works in museums and collections

MNCARS, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid. Colección ING, Ámsterdam. Museum of Contemporary Photography, Chicago, E.E.U.U. Williams College Museum of Art. Williamstown. Massachusett. The Centre National d'Art et de Culture Georges-Pompidou de Paris. Francia. Le Centquatre (EPCC) Paris, Francia. The Margulies Collection, Miami, E.E.U.U. Caldic Collection, Rótterdam, Holanda. Colección Neuflize Vie, Paris, Francia. Song Eun Art Foundation, Seúl, Corea del Sur. The Busan Museum of Art. Busan Corea del Sur. Contemporary Art Collection University of California, E.E.U.U. Fundació Pilar i Joan Miró, Mallorca. West Collection, Oaks, E.E.U.U. IVAM. Museo Arte Contemporáneo Valencia. CAC de Málaga, etc.