The DHaus Company: The Proposal

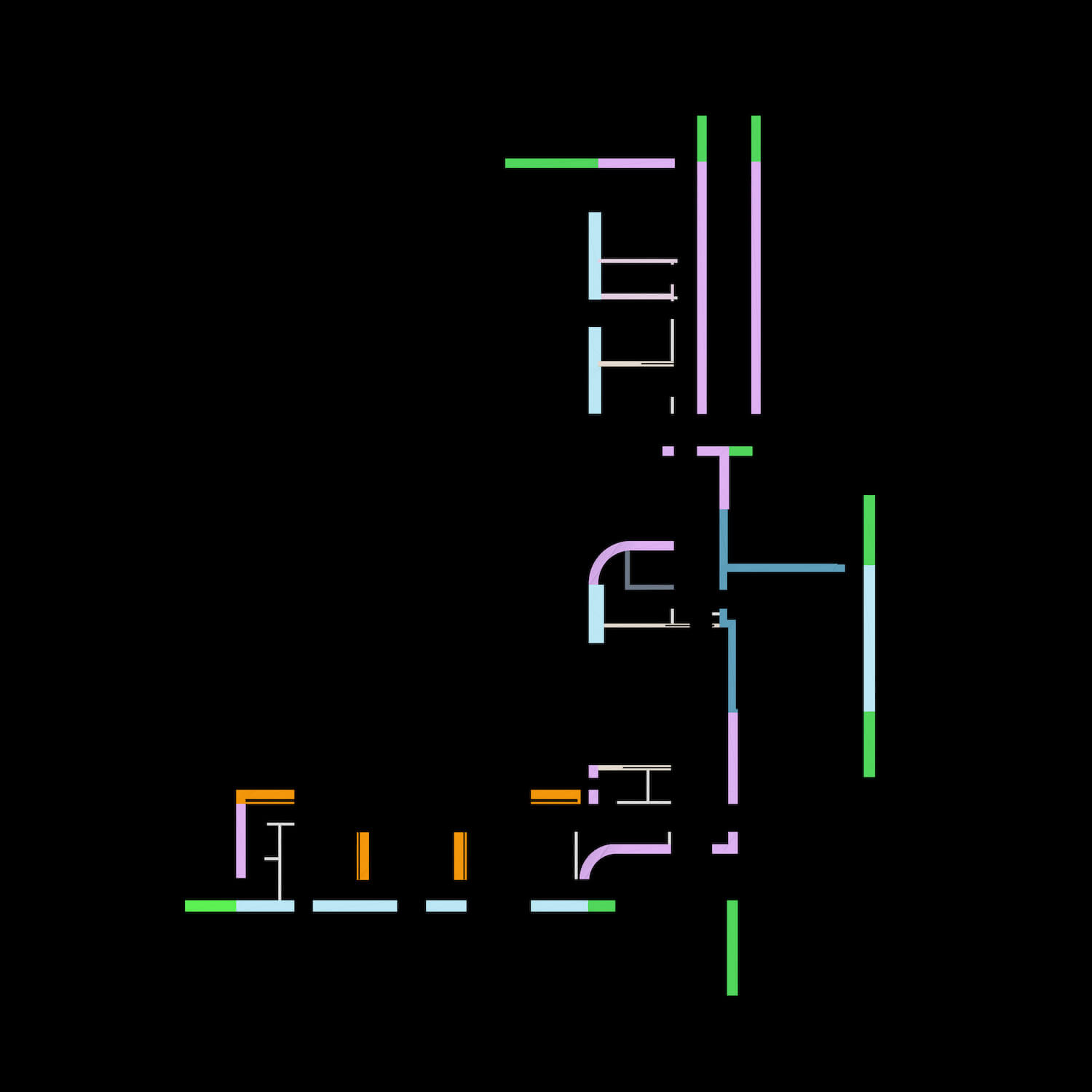

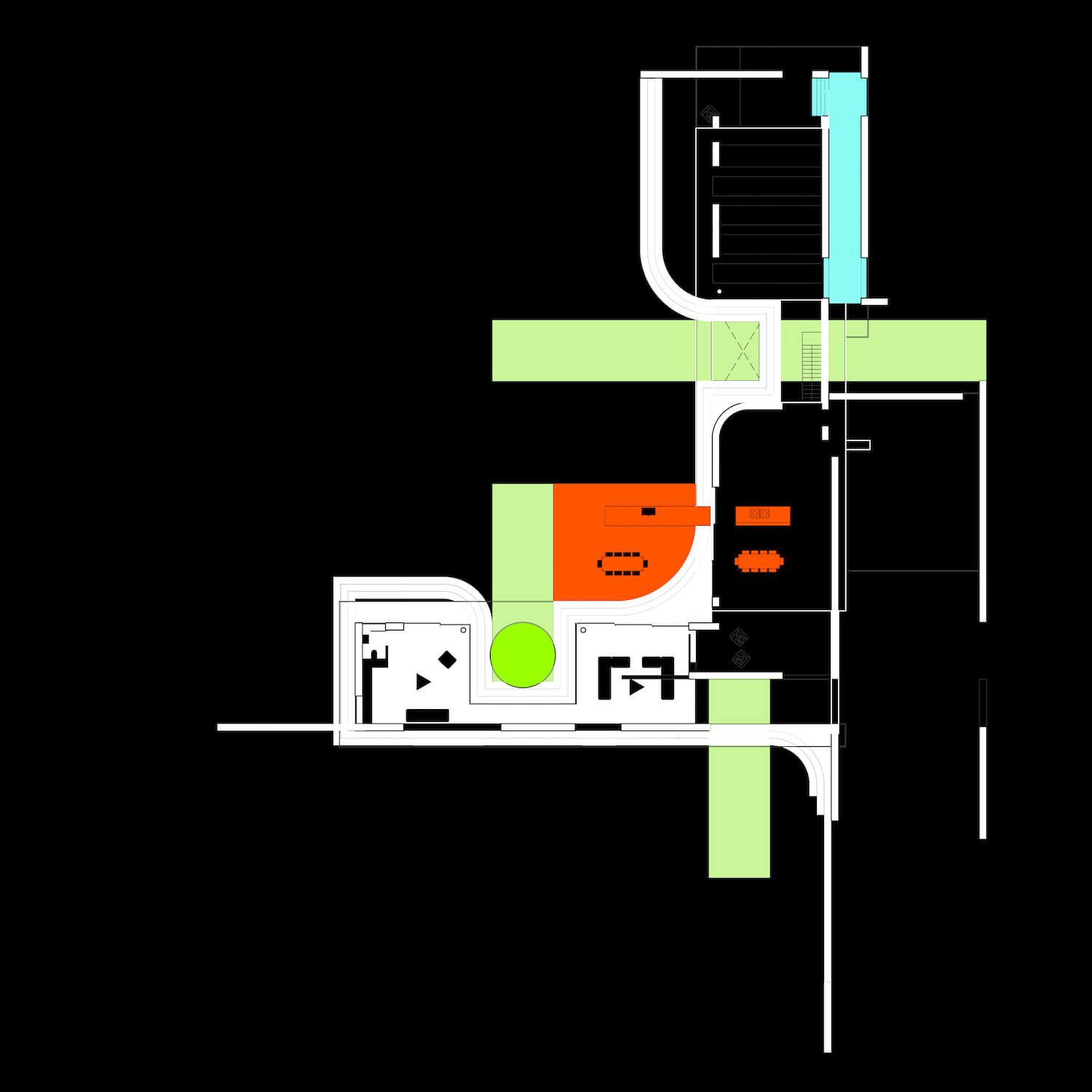

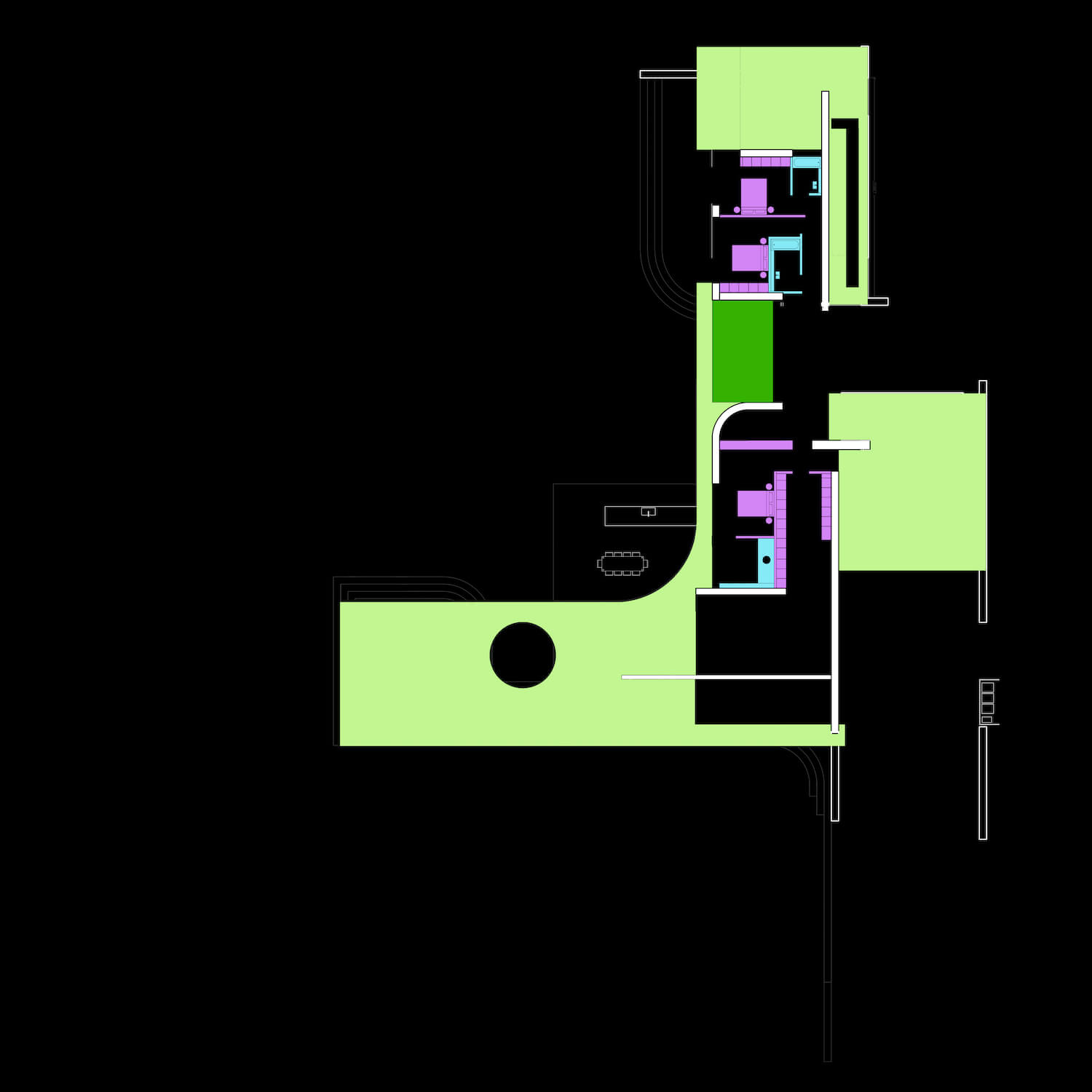

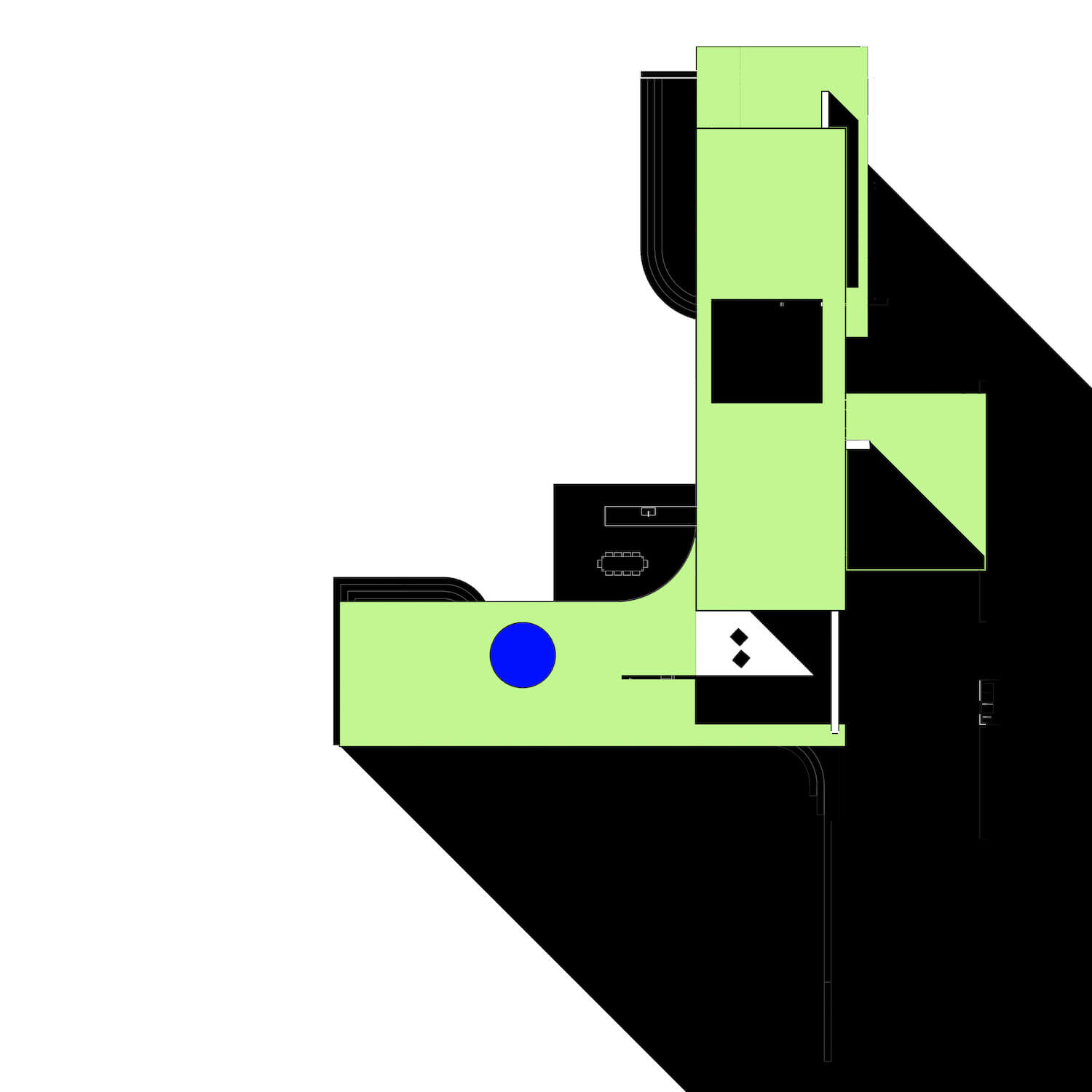

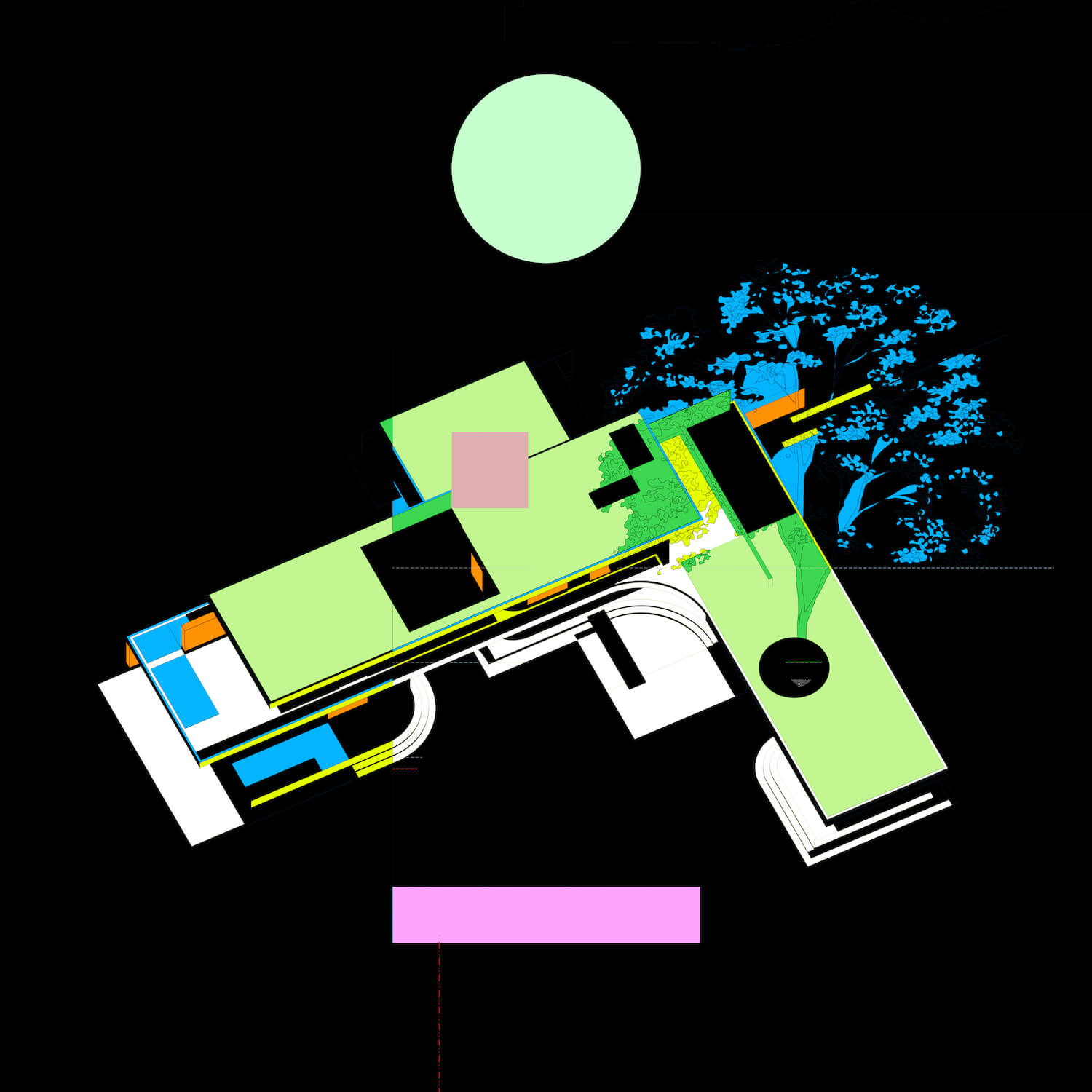

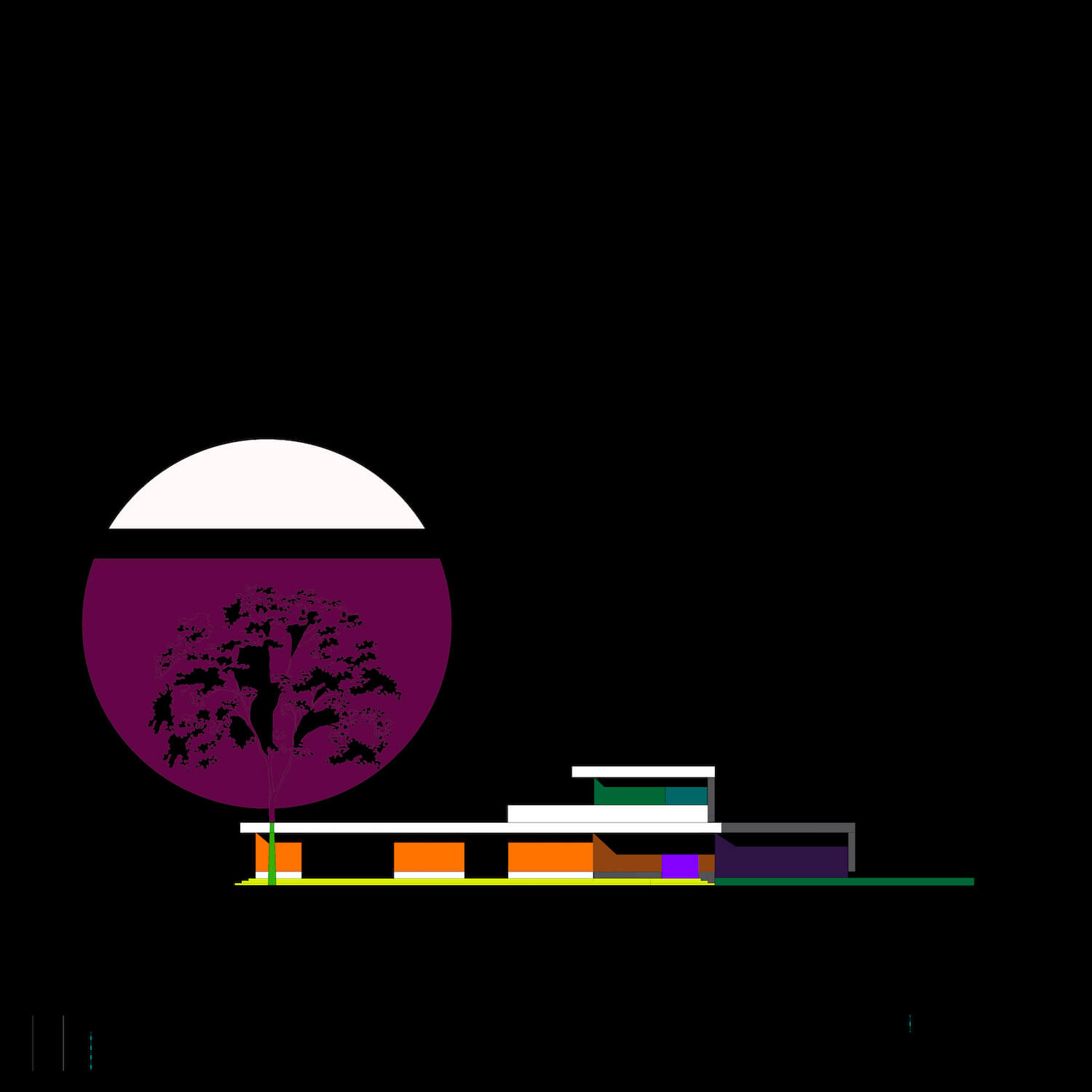

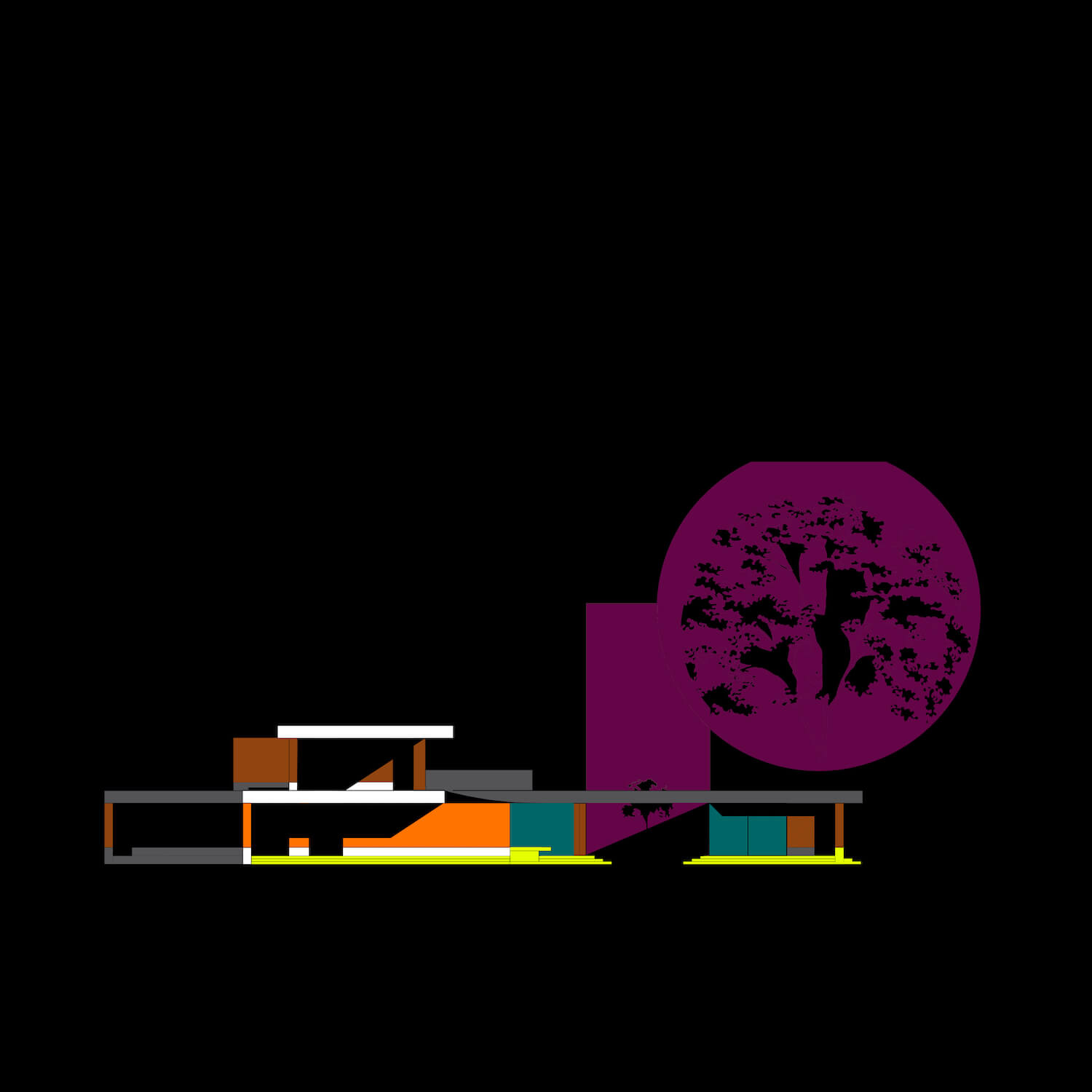

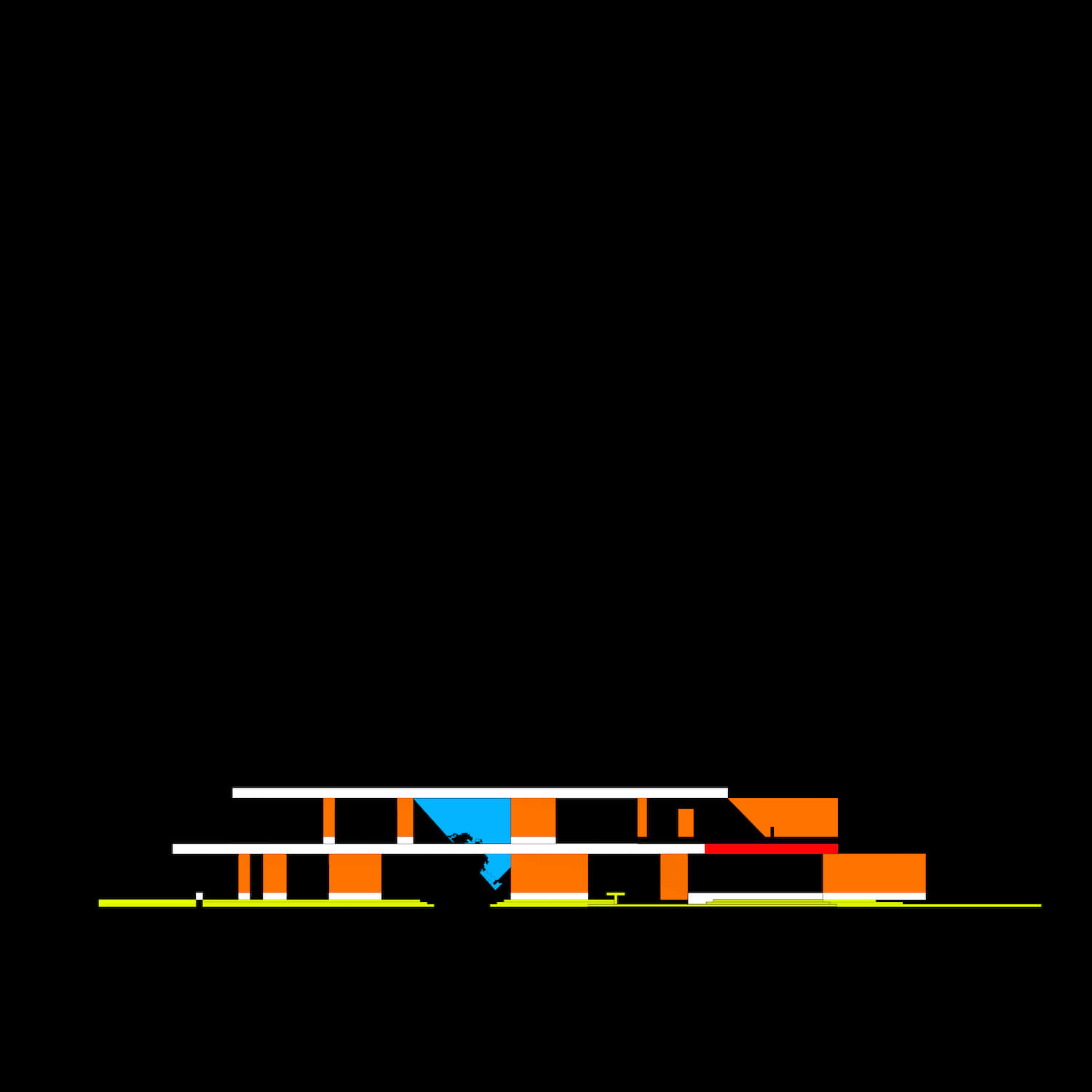

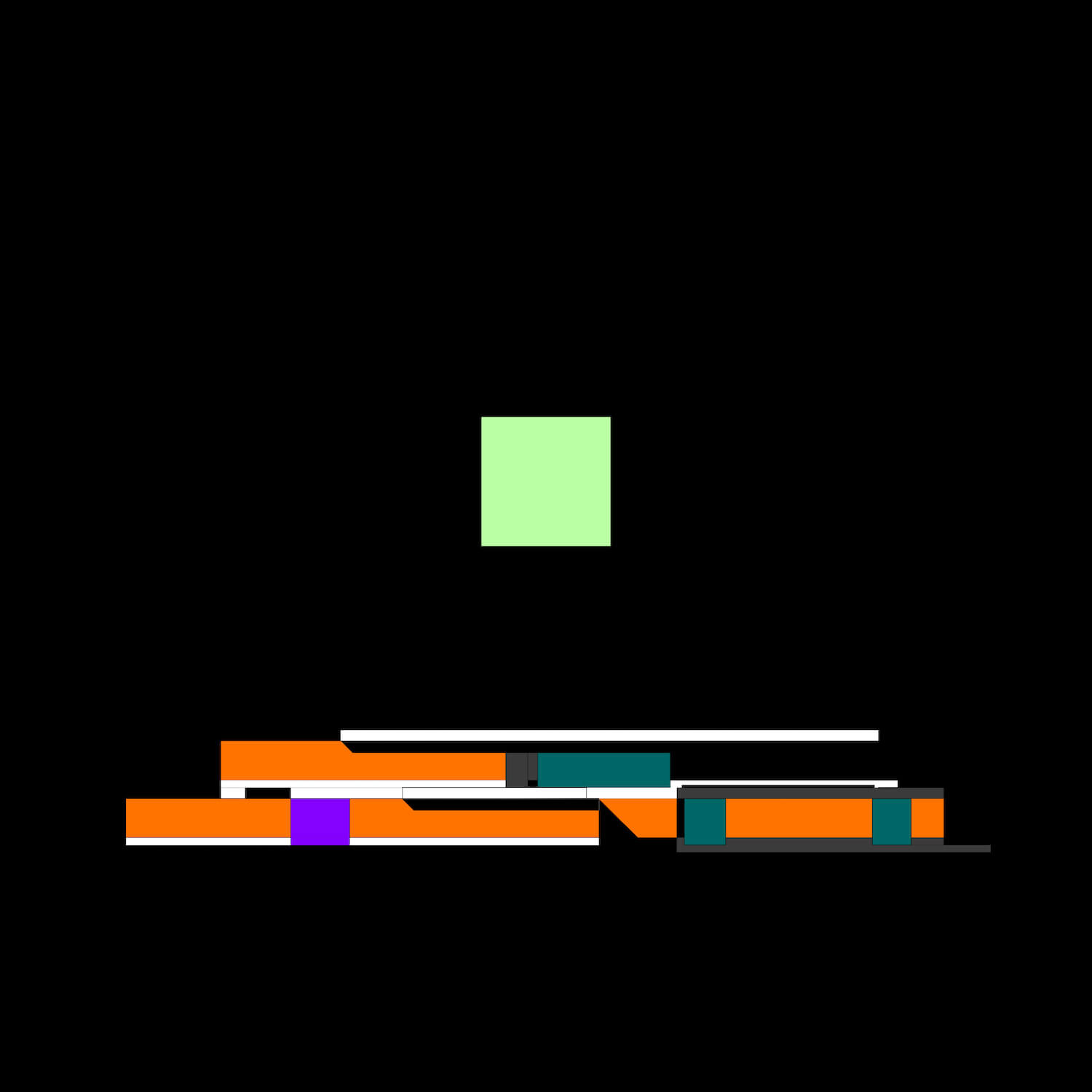

La Terre is a one-off new build home in an AONB in Surrey, Southern England. The four-bedroom home has an elevated ground floor, set 0.5m up from the grass, like the Farnsworth house or other 1940 / 50s case study homes where the architecture appears to be weightless and floats.

Special attention was paid to this idea of raised living, the accessible steps raise the structure and form sculptural elements. These sculpted steps meander in and out of the living areas like a river of programme.

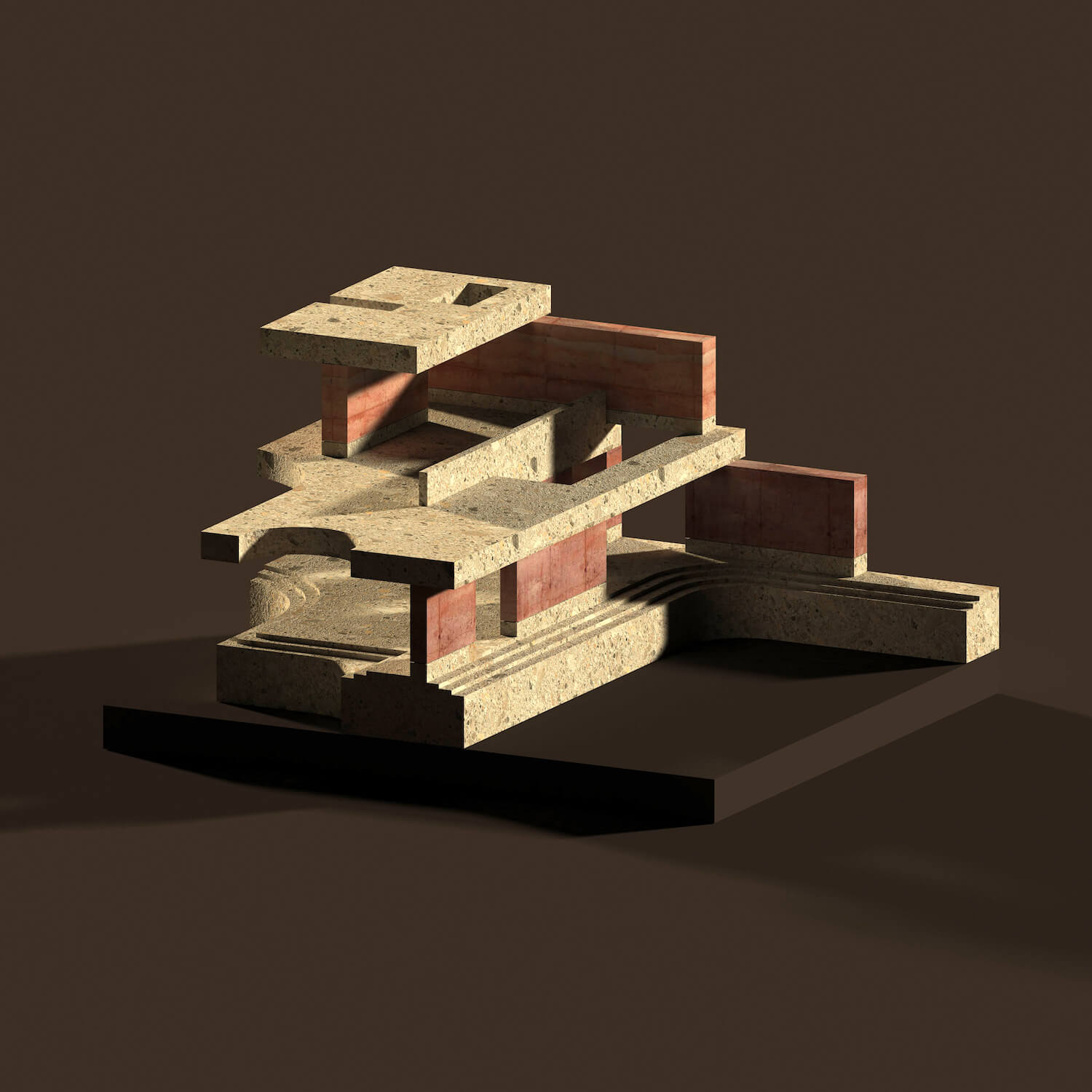

Cast concrete plinths form the basis of stabilised earth walls, preventing erosion and providing a structural datum which is expressed around the building perimiter Two large atriums allow Japanese gardens into the circulation spaces so that one feels as if they are walking outside in the landscape when moving throughout the house. Planning is approved and we look forward to starting construction summer 2023.

Rammed Earth

Earth is one of the world’s oldest building materials and most ancient civilizations used it in some form. It was easily available, cheap, strong and required only simple technology. In Egypt the grain stores of Ramasseum built in adobe in 1300BC still exist; the Great Wall of China has sections built in rammed earth over 2000 years ago. Iran, India, Nepal, Yemen all have examples of ancient cities and large buildings built in various forms of earthen construction.

It is significant that the oldest surviving examples of this building form are in the most arid areas of the world. The strength of unstabilised earth walls comes from the bonding effect of dried clay. If this becomes wet the strength is lost and indeed the wall will erode or even fail completely. Different countries have different approaches to this problem.

Stabilised Rammed Earth is a modern development of one of the oldest building materials known to man. Modern technology, modern machinery and 30 years of development have created a masonry wall material that is attractive, environmentally beneficial and meets European building regulations. Stabilised rammed earth can have the appearance of cut stone, the strength of concrete and the weather resistance of brick; yet environmentally outperform any of these. Initially developed to compete with brick for low-cost housing, Stabilised Rammed Earth is now being used by:

governmental bodies seeking eco-friendly building methods

architects seeking the latest attractive materials

clients wanting overall energy efficiency

In England there is ample evidence of earth’s use as a building material, as around 60% of scheduled “ancient monuments and archaeological sites” are constructed of earth or have earthworks associated. But it became regarded as a material of limited durability and thus inferior to more permanent materials, such as stone or fired clay bricks. Consequently, within the last few centuries, it has most commonly been used for workers cottages, barns and perimeter walls where cost was more important than longevity. This is evident from the fact that fewer than 2% of the 450,000 listed buildings in England are made of earth.

The modern version of earth building, which is stabilised to solve the long-standing problem of solubility, has developed through an interesting set of international connections. An English trained Architect and Engineer, George Middleton, worked at the Experimental Building Station in Sydney in the late 1940’s. Looking for methods of building low-cost housing, he experimented with stabilising earth and produced a publication from the Station: “Bulletin 5, Earth Wall Construction”, which eventually became a standard reference for earth building in Australia. In 1953 he published a book: “Build Your House of Earth; A Manual of Earth Wall Construction”, which has been reprinted several times. Middleton advised the Israelis on low-cost housing and their developments were published in “Soil Construction – Its Principles and Application for Housing” in 1957 by S. Cytryn.

This publication, which introduced the term Stabilised Rammed Earth, came to the notice of the architect Tom Roberts and artist Giles Hohnen in 1975 in Western Australia. Their interest in earth-wall building started with the search for an aesthetic and cost-effective wall material for a new Winery at Margaret River. Western Australia at the time was a “brick and tile” state, with the only other option, timber frame, viewed as a “low rent” building material, actively discouraged by local councils. This, combined with the 1973 OPEC oil price hikes (prices quadrupling between 1973 and 1974 and rose a further 150% in 1979 in the wake of the Iranian Revolution) created an inflationary period that the brick industry seemed to be cheerfully exploiting

Apart from jacking prices, they were able to dump failed experiments in brick and tile fashions on the country builders and Margaret River was facing a creeping rash of what they called “ tropical disease” houses with speckled mixes of brown, cream, white, pink and green walls and roofs.

Based on Cytryn’s advice, these men took the critical decision to use local lateritic gravel and stabilise it with a low percentage of (approx 2-3% initially) cement rather than use earth with 40% clay as had been done previously in Australia. They built a shed in Stabilised Rammed Earth at Cape Mentelle in 1976 to demonstrate to the Council the durability and strength of the material, which still stands today in pristine condition unaffected by the weather. The following year the council approved the construction of the first stage of the winery and within 10 years approximately 20% of new houses in the shire were of SRE. This was the start of a SRE building boom in Margaret River, Western Australia, where within a few years, 20% of new houses were being built in this new material.

Note from the client:

‘‘It was love at first sight; we arrived at the site, and looked, across the meadow. We were ankle deep in the long grass, which was shared with of birds strutting, feeding, crowing, landing, taking off all around. And off in the middle distance. We were overwhelmed when we thought that perhaps we create a beautiful new home here, We are keen gardeners and want to preserve and enhance this beautiful plot of land,

This inspired a dream. A dream in which we could create a unique and beautiful house but, as importantly, a home where we could spend the rest of our lives in the Farnham communities. We needed to build a house to suit our health needs as we grow older, but that did not mean that it should be boring, ordinary or just practical. We recognised the challenges of climate change and the goal of improved sustainability and judged that any modernisation of the current barn would not enable it to be fit-for-purpose.

Rather, we passionately want to build a one-of-a-kind contemporary home fully doing justice to this unique location, and one that enables us to live an enriching life, whatever our physical or mental limitations, in wonderful surroundings. For the last few months, we have been on a really interesting journey with a dynamic inspirational team of architects and a team of local, national and international experts whom we have gathered together.”

What are the sustainability features?

La Terre utilizes renewable resources and passive house principles to achieve low energy consumption.