Merrell Soule Architects: Sun Valley, Idaho, is a popular stopover on the migratory flight path of west coast celebrities and the bi-coastal CEOs for cutting-edge tech and entertainment firms, who love the outdoors. In winter, the ski slopes are dotted with famous movie characters while in mid-summer, during the ten-day Allen & Company conference, the tarmac at nearby Hailey’s airport is covered with hundreds of private “birds,” as if nesting season has arrived. In this creative setting, the opportunity to design a house with interior designer Ellen Hanson, for her and husband Richard Perlman, chairman of Examworks, came with the challenge to reinterpret the typical ski house, and its relationship to this dramatic landscape. Existing architectural styles held no attraction.

For Hamptons, NY, architect James Merrell, the project was a welcome change of pace. During his first trip west he arranged to meet with the local builder already selected for the project, Kavanagh Construction’s owner, and Marlboro Man look-alike, Dennis Kavanagh. This meeting had been proposed as a formality: to meet the team. But Kavanagh had other ideas for his out-of-town guest, and quickly turned it into a crash course on the region’s unique high desert climate and related topics, from seismic shifts and snow loads, to infra-red solar radiation and much more. This crash course took two days! But it became the inaugural event in the story of this unique design.

Ski house architecture typically recalls the chalet, with its gently sloping, wing-like roof planes. This reference is embedded in our minds, and appears in increasingly cartoonish, and loggy, form throughout the Rocky Mountains. But Merrell had not imagined a chalet-derived design, and surprisingly, Kavanagh reinforced his thinking, pointing out that large sloping roofs actually amass snow, which in turn promotes mini-avalanches that decimate plantings and occasionally seriously injure residents and caretakers alike. In fact, Kavanagh noted, he was currently acting as an expert witness on just such a case, involving a movie star’s house designed by architects from Texas. So there was unanimous support for a different approach.

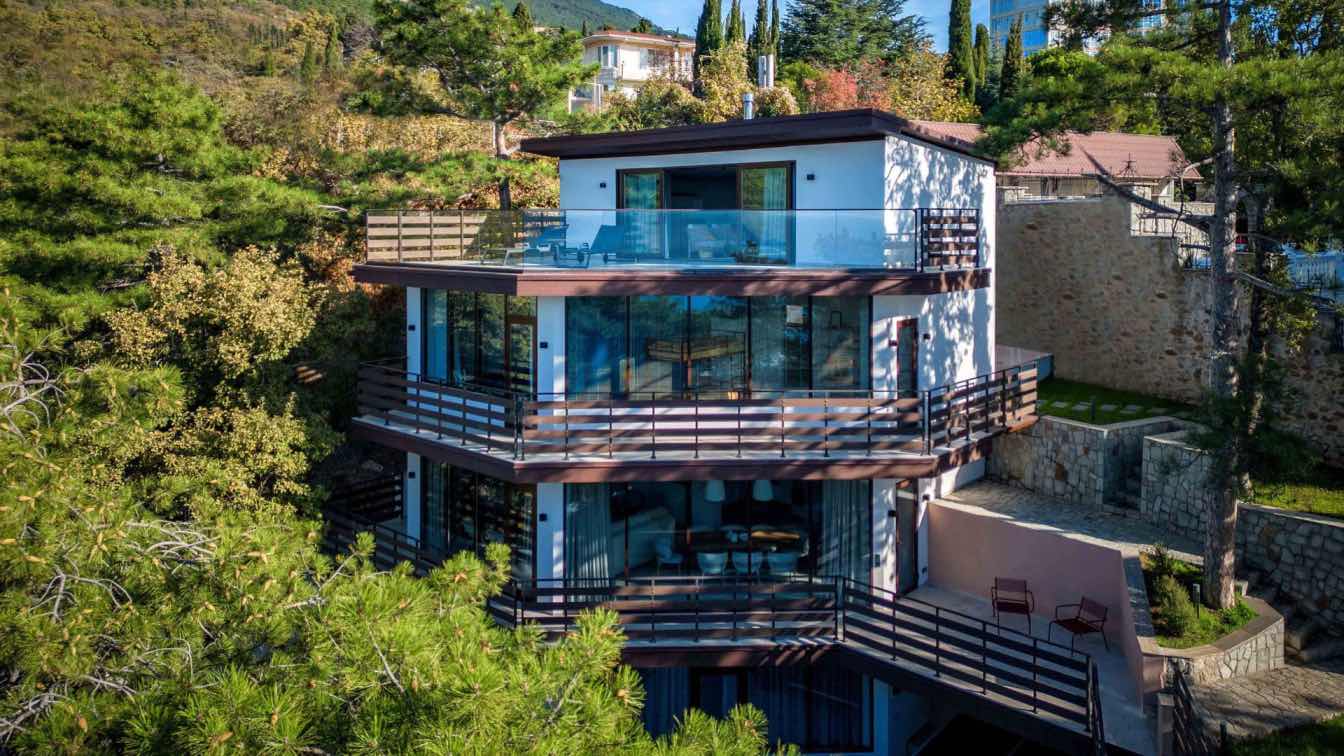

Having jettisoned the chalet-vernacular Merrell also passed on the international-style influence that had become popular in recent years. Merrell and Hanson both wanted a contemporary house, but one that would resonate with regional flavor. During frequent summer hikes on the area trails, especially hikes up Adam’s Gulch to Cathedral Rock, they were inspired to take architectural cues instead from the rock promontories there. The site of the house was steeply sloped, like the gulch, and the house wanted to stretch up vertically to get panoramic views. A simple vertical mass, they decided, growing upward out of the hillside would echo these formations and work beautifully.

As this idea took shape they grounded the design with a series of horizontal board-formed concrete walls that supported both the house and the terraces needed for the steep entry yard. Then, a large vertical wall of glass was carefully aimed at the primary valley view, with secondary glass sheets aimed off toward other peaks and valleys. And, a sheet metal skin of oiled steel was selected for the siding, to bring in the dark tones of the stone masses that had been so inspirational. (Kavanagh loved the oiled-steel siding, noting the high desert sun burns paint off of traditional wood siding almost instantly, and the maintenance is constant.)

With the design coming together, Merrell and Hanson still had one final concern: energy consumption. For anyone with multiple homes, energy consumption is both a practical and an ethical concern. And for a glassy house like this one, in an extreme environment, meeting this challenge would be critical. In the high desert the sun plays a complicated role. Solar gain on a cold winter’s day can start up air conditioners when the sun hits a large window. But a moment later, when a cloud passes over and sub-zero air temps reverse this condition, heat may be needed. In this location freeze thaw cycles, which in the Hamptons occur only daily, can happen dozens of times a day. So, designing for energy efficiency required a close focus on the sun: solar gain through windows, and infra-red radiation through the walls and roof planes.

Here again, Kavanagh had a unique resource. In that introductory meeting he had subjected Merrell to at least a half day with former NASA scientist and local infra-red radiation evangelist, Art Carlson. “Did you know that John Glenn returned from his first orbit of earth with a sunburn?” asked Carlson. Apparently that was a well-kept secret, and subsequent space capsules were quickly lined with aluminum foil, successfully reflecting infra-red radiation on future missions. “Think of a glass thermos!” he said. “Think of those reflectors people put in their windshields!” Carlson was convincing.

With this perspective in mind, the house walls were detailed with two layers of high emissivity reflective foil and airspaces: one layer facing out and another one facing in. Though Carlson had suggested that insulation would not be needed, the walls were nevertheless filled with spray foam insulation “to appease the local building officials.” And, to control infra-red gain through the windows, a task for which window tinting is worthless, automated blinds were fitted with a high-emissivity fabric to reflect solar radiation when deployed. These blinds cover all large windows and are deployed to great effect when the house is unoccupied. With all the architectural lighting in the house using LED technology, the resulting energy stats have been remarkable.

Finally, Merrell and Hanson turned their attention to the interior architecture finishes, and Hanson to the art and furnishings for the house. Continuing the theme of regional resonance, the interior windows, doors and trim were all constructed of Alaskan Yellow Cedar, bringing a buttery wood tone to the interiors. Accent walls and flooring employed local walnut and hickory: character grade. The main fireplace hearth became one gigantic rugged stone, quarried in the region, while secondary fireplaces of oiled-steel recall the wood stoves of mountain cabins. But this interior detailing was all kept intentionally minimal so the house would not to compete with the views.

Hanson extended the same aesthetic into the art and furnishings. The artful American flag over the living room fireplace and the ceramic shades over the dining table both express her interest in contemporary craft work. The leather wrapping of the metal handrail along the entry stair was crafted by a local saddle maker. The rugged barn wood in the breakfast table, and many other touches, all reiterate the lifestyle values shared by many who love this valley. All in all, this design is both regional and minimal. And the team believes, with its unique design features and technologies, it offers an exciting new model for high desert living.