Based in Madrid, Spain, and the founder of Cervera Arquitectos, architect Rosa Cervera has designed distinguished projects across the globe in Russia, Spain, China, India, Malaysia etc. She has been equally charged and on the forefront in architecture education as a professor at the University of Alcala, current Director of Master’s in Advanced Design, former Dean of the School of Architecture and a former Visiting Fellow/Scholar at the Columbia University and University of Miami respectively. A recipient of a number of international/national awards, her “innovative architecture promotes new models for ecological design, respecting both nature and human needs.”

Architect/academician Rosa Cervera has had the privilege of delivering lectures/talks in universities and institutions in Europe, Asia and America. She has authored books on architecture and professional articles to magazines/journals. Applying Bionics and Biometrics to architecture has always been a focus in her practice.

Suneet Paul- editor/architect/author and former editor-in-chief of Architecture + Design, recently had an interesting chit-chat with her. Excerpts of their interaction:

Suneet Paul: First of all, please accept my acknowledgements for having so dedicatedly and passionately contributing to the mystic and creative process in architecture and simultaneously pursuing your love for academics in architecture. How’s the journey been?

Rosa Cervera: From a young age, I have been deeply engaged in architectural education, balancing it alongside my professional practice. After completing my doctorate, I had the opportunity to enter academia and quickly realized how teaching and professional practice could enrich each other in a cycle of mutual improvement. The academic field fosters continuous exploration, idea exchange, and an innovative mindset, all of which open new doors that might not be visible through practice alone. Architecture, much like medicine or law, is a field that thrives when academia is intertwined with active professional work. Research also plays a crucial role in complementing both teaching and practice. Although it requires a long-term process and experimental spaces, research serves as a vital laboratory that ultimately nourishes architectural practice, enabling it to adapt to fast-paced demands and societal needs. I have been fortunate to combine professional practice with teaching and research throughout my career, and I always encourage my students not to lose sight of the importance of research.

Xixi Hotel Boutique, Hangzhou, China

Xixi Hotel Boutique, Hangzhou, China

SP: Having worked on projects in different countries, adapting architecture and design to the cultural context of that respective country must have been a pleasing challenge. Of course, the vocabulary of global architecture all across is in great demand. Your experience-.

RC: Our first opportunity to work outside Spain came in the mid-90s, after completing several unique and innovative projects domestically. This new project was the headquarters for the National Savings Bank, Sberbank, located in Voronezh, in the newly formed Russian Federation. The country’s desire for modernization following perestroika was to be expressed through architecture, giving us the chance to design a building in the city’s most prominent area. This building, commemorating the 300th anniversary of Peter the Great’s establishment of the Russian fleet, has since become a landmark in the city. The working conditions were quite unique, requiring us to adapt and maintain a flexible approach to find common ground.

In 2000, we won the competition for the new Chinese Embassy in Spain, which opened the door for our entry into China. From that point on, our activity in the country was intensive—starting with lectures and exhibitions, and soon moving to competitions where we not only participated but also won and built several projects. While architecture is a global discipline and many foundational principles are universal, we found that traditions, work methods, communication styles, and regulatory frameworks in Spain and China were quite different. We immersed ourselves in Chinese culture to absorb its core principles, and at the same time, China's drive for avant-garde contributions from foreign architects allowed us to develop engaging projects of various scales and explore new creative opportunities. My personal interest in China has never waned; I continue to visit regularly, witnessing its tremendous and rapid transformation. I am still actively studying and researching its culture and architecture, and at one point, I even felt it worthwhile to study Mandarín Chínese.

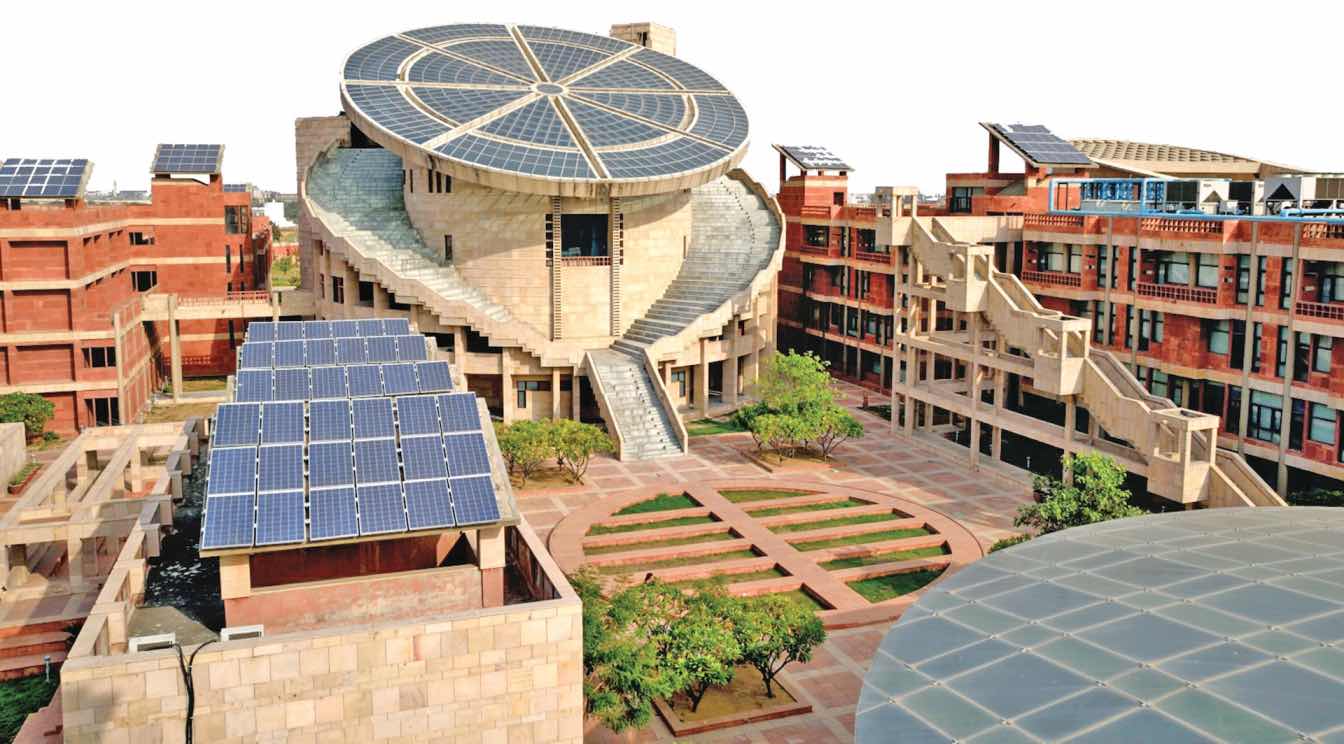

My passion for India was sparked in my youth during my first visit as a university student on a study trip. Fortunately, my professional path led me back there in the early 2000s, launching a significant chapter of architectural work. Projects in Delhi, Kolkata, Mohali, and Pune—some of substantial scale and fully realized—have engaged years of my career in what has been an exciting adventure. These projects allowed us to apply research into the efficiency of natural forms directly to practice, creating an innovative repertoire inspired by nature’s geometry. With flowing shapes and gentle curves that move beyond the standard box form, these designs significantly reduce embedded energy in their structure and lower operational energy consumption. Collaborating with local colleagues added yet another layer of richness to this journey, allowing us to integrate a deeper understanding of both design and context. My interest in India even led me to study its urban landscape in depth and to co-author the book Re-envisioning Mumbai with university colleagues. Today, I continue to travel to India and am actively involved in the academic community, frequently visiting and honored to have been appointed an honorary professor at LPU University in Punjab.

Lastly, I would like to highlight my experience in Bolivia, a very different setting where we realized an urban project in collaboration with the local community in the area around Santa Cruz de la Sierra. This highly engaging participatory process involved professionals working to translate the aspirations of modest communities needing support to improve their vulnerable surroundings. This project was especially meaningful, and we were honored to receive a major recognition for it in 2017.

Central One, Gurugram,India

Central One, Gurugram,India

SP: I remember many years back, in our first introductory meeting in Madrid, your research on the design of the Bionic Towers was in full swing. Would you like to elaborate a bit on the fructification of the project now, and how well does it fit in the future-scape of urbanity specially when there is so much talk about sustainability and control of carbon emissions?

RC: The Bionic Tower (Cervera & Pioz Architects) represents a pinnacle of our research in natural forms and proposes an entirely new model of vertical urbanism. This project offers the infrastructure for vertical urban development, providing living space for up to 100,000 people. By moving beyond the concept of the super-skyscraper, it creates an urban environment that grows vertically, aiming fundamentally to reduce land consumption amid the relentless, land-intensive expansion of cities worldwide. This model aims to return land to nature by using territory more efficiently in densely populated areas. We could say it’s unfair to pave over the planet.

Inspired by natural structures, the design achieves an innovative bio-structural model reaching 1,228 meters in height with 2 million square meters of constructed space. This vertical structure functions as a "city within a city," integrating residential areas, offices, hotels, commercial spaces, and public amenities into a cohesive, self-sustaining urban ecosystem. Through 368 elevators that move both vertically and horizontally, it seamlessly connects 12 independent neighborhoods, offering the vibrancy and functionality of a traditional cityscape in a vertical form. It emphasizes public spaces and plazas, an intelligent, low-consumption vertical transport system, and an integration of greenery in the form of gardens that ascend throughout the complex. These vast dimensions also enable a high level of energy self-sufficiency.

The Vertical Garden City Bionic Tower is a new interpretation of the roles that architecture and urban planning should play in creating an eco-habitat, balancing nature and technology. This approach envisions a sustainable future rooted in our shared origin—the Earth—while looking forward to what architecture can offer the cities of tomorrow.

The present moment demands a renewed approach to our relationship with nature, one that fosters sustainable, balanced coexistence. Nature embodies efficiency, minimizing material as a core principle for energy conservation and survival. Why not learn from these natural mechanisms to "achieve more with less effort"? My architectural journey has been about trying to imitate the principles of efficiency found in nature, reducing both embedded and operational energy. In this sense, the Bionic Tower has been a true field of experimentation.

Research into biological structures, like bones, shells, and trees, has led to new architectural models that reduce material and energy use by 30% or more compared to traditional designs. This approach opens new possibilities for efficient, sustainable construction. Today, I am taking a further step in this direction with architecture that incorporates the cultivation of living organisms, such as microalgae, into its elements. The goal is for architecture to also function as an energy factory, absorbing CO2, offsetting carbon footprints, and generating biomass, in a further move towards sustainability.

Embassy of PR China in Madrid, Spain

Embassy of PR China in Madrid, Spain

SP: In the Indian scenario, admissions to the courses of architecture are dwindling dramatically due to a variety of reasons – renumeration issues, bleak future in comparison to other professions, resultant inferior faculty inputs and such others. How is it in Spain?

RC: The profession has changed profoundly. The expectations of my generation, where we aspired to create our own architecture from day one, are now largely out of reach for today’s graduates. In my view, several factors have driven this shift, with one of the most significant being the concentration of work within large “architecture factories.” This model prevails internationally, with major firms employing thousands, and on a national level, where companies have hundreds of employees. These large firms enjoy a considerable advantage in bidding for projects that often require not only talent but also a high level of revenue and a solid portfolio of completed projects. This effectively bars young professionals, who, in addition to talent, need a track record they have yet to build.

Additional factors also contribute to the diminishing value of the architectural profession. The allure it held in the late 20th and early 21st centuries—amplified by high-profile figures with significant media visibility—drew in many students, leading to an increase in architects that now far exceeds society’s demand. This has been compounded by a growing emphasis on economic factors that prioritize cost savings and reduced professional fees over the quality of urban planning and architecture. Consequently, career prospects for recent graduates are limited, prompting many to consider other fields that offer greater job stability and financial security..

Spain is also experiencing this trend, which I believe is global. From the previous generations, where the architect held a respected role for their societal contributions, to my generation, which had opportunities to achieve a fair balance between effort and reward, today’s young professionals face a long, intense path of preparation only to receive limited recognition and compensation.

Taisa Plaza, Chengdu, China

Taisa Plaza, Chengdu, China

SP: I have personally never dwelt upon architecture based on gender as it is an end-product of human creative urges/energies. However, opportunities could and probably do differ in society based on instinctive biases. In India, there is a strong wave in the architecture/design media highlighting achievements of women architects. Your response to: (a) Is there an emotive difference in the approach to design based on gender and (b) Being a woman, have you experienced any differential approach by clients or then in the award of a project?

RC: Architecture, as a discipline, has no gender, but the actors involved in it do. Throughout history, architecture has largely been the work of men, while women have mostly been excluded. However, this has changed in contemporary society, as women have moved out of the domestic sphere and integrated into all aspects of social life, taking on roles that, or should be, or already are, equal to those of men, with full recognition from society.

It is important to note, however, that many women have been erased from the history of architecture, and this invisibilization has contributed to the perception that architecture is an exclusive domain of men. There are countless examples of women who made significant contributions to architecture, yet their work remains largely unknown. In many cases, this erasure came from their own colleagues, critics, historians, and even male peers, who, instead of recognizing them as equals, pushed them into obscurity. It is essential to recover and highlight this historical legacy as a right of the women who made such significant contributions. Likewise, it is crucial to value the work that the current generation of female architects is carrying out today.

In my particular case, I began practicing architecture at an interesting moment in Spain’s history, during a time of recent democracy with new social changes, where women were fully recognized in terms of their rights, abilities, and freedoms. This context allowed the professional work of female architects to be accepted without any obstacles. It is true that we were clearly a minority, both in university and later in the profession, and even more so in construction, where the workforce continues to be predominantly male. Throughout my career, with a few ocasional exceptions, I haven’t encountered obstacles from clients or construction workers. However, I must say that the most challenging situations have often come from my colleagues and peers. Perhaps within the professional and intellectual circles, there was a more subtle resistance to recognizing the contributions of women and acknowledging their ability to excel. Women were often assigned the role of diligent workers, while the role of creative visionaries was reserved for men —a notion that is entirely unfounded and often masks underlying frustrations among male colleagues. And, perhaps, this is still an unfinished business. That is why efforts to promote and highlight the work of women architects are necessary.

SP: Thank you for sharing across your insightful thoughts and specially your beliefs on the status of women architects in this profession. I’m sure with more women architects/designers coming to the forefront, the equations would find a balancing ground.