Diébédo Francis Kéré, architect, educator and social activist, has been selected as the 2022 Laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize, announced Tom Pritzker, Chairman of The Hyatt Foundation, which sponsors the award that is regarded internationally as architecture’s highest honor.

“I am hoping to change the paradigm, push people to dream and undergo risk. It is not because you are rich that you should waste material . It is not because you are poor that you should not try to create quality,” says Kéré . “Everyone deserves quality, everyone deserves luxury, and everyone deserves comfort. We are interlinked and concerns in climate, democracy and scarcity are concerns for us all .”

Born in Gando, Burkina Faso and based in Berlin, Germany, the architect known as Francis Kéré empowers and transforms communities through the process of architecture. Through his commitment to social justice and engagement, and intelligent use of local materials to connect and respond to the natural climate, he works in marginalized countries laden with constraints and adversity, where architecture and infrastructure are absent. Building contemporary school institutions, health facilities, professional housing, civic buildings and public spaces, oftentimes in lands where resources are fragile and fellowship is vital, the expression of his works exceeds the value of a building itself.

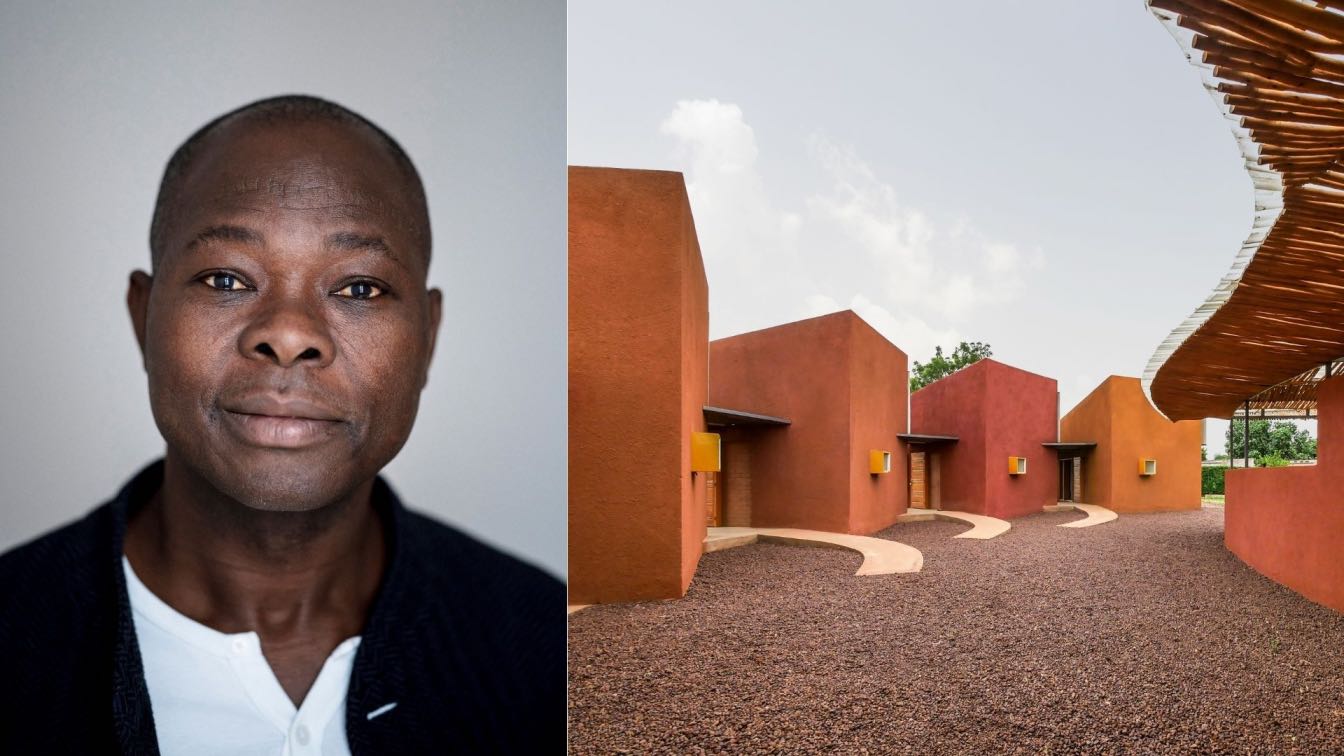

Diébédo Francis Kéré, photo courtesy of Lars Borges

Diébédo Francis Kéré, photo courtesy of Lars Borges

“Francis Kéré is pioneering architecture - sustainable to the earth and its inhabitants - in lands of extreme scarcity. He is equally architect and servant, improving upon the lives and experiences of countless citizens in a region of the world that is at times forgotten,” comments Pritzker. “Through buildings that demonstrate beauty, modesty, boldness and invention, and by the integrity of his architecture and geste, Kéré gracefully upholds the mission of this Prize .”

Gando Primary School (2001, Gando, Burkina Faso) established the foundation for Kéré’s ideology – building a wellspring with and for a community to fulfill an essential need and redeem social inequities . His response required a dual solution – a physical and contemporary design for a facility that could combat extreme heat and poor lighting conditions with limited resources, and a social resoluteness to overcome incertitude from within the community . He fundraised internationally, while creating invariable opportunities for local citizens, from conception to vocational craftsmanship training . Indigenous clay was fortified with cement to form bricks with bioclimatic thermal mass, retaining cooler air inside while allowing heat to escape through a brick ceiling and wide, overhanging, elevated roof, resulting in ventilation without the mechanical intervention of air conditioning . The success of this project increased the school’s student body from 120 to 700 students, and catalyzed Teachers’ Housing (2004, Gando, Burkina Faso), an Extension (2008, Gando, Burkina Faso) and Library (2019, Gando, Burkina Faso).

Léo Doctors’ Housing, photo courtesy of Francis Kéré

Léo Doctors’ Housing, photo courtesy of Francis Kéré

The 2022 Jury Citation states, in part, “He knows, from within, that architecture is not about the object but the objective; not the product, but the process . Francis Kéré’s entire body of work shows us the power of materiality rooted in place . His buildings, for and with communities, are directly of those communities – in their making, their materials, their programs and their unique characters .”

The impact of his work in primary and secondary schools catalyzed the inception of many institutions, each demonstrating sensitivity to bioclimatic environments and sustainability distinctive to locality, and impacting many generations . Startup Lions Campus (2021, Turkana, Kenya), an information and communication technologies campus, uses local quarry stone and stacked towers for passive cooling to minimize the air conditioning required to protect technology equipment . Burkina Institute of Technology (Phase I, 2020, Koudougou, Burkina Faso) is composed of cooling clay walls that were cast in-situ to accelerate the building process . Overhanging eucalyptus, regarded as inefficient due to its minimal shading abilities yet depletion of nutrients from the soil, were repurposed to line the angled corrugated metal roofs, which protect the building during the country’s brief rainy reason, and rainwater is collected underground to irrigate mango plantations on the premises .

The national confidence and embrace of Kéré has prompted one of the architect’s most pivotal and ambitious projects, the National Assembly of Burkina Faso (Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso), which was commissioned, although remains unbuilt amidst present uncertain times . After the Burkinabè uprising in 2014 destroyed the former structure, the architect designed a stepped and lattice pyramidal building, housing a 127-person assembly hall on the interior, while encouraging informal congregation on the exterior . Enabling new views, physically and metaphorically, this is one piece to a greater master plan, envisioned to include indigenous flora, exhibition spaces, courtyards, and a monument to those who lost their lives in protest of the old regime .

Centre for Health and Social Welfare, photo courtesy of Francis Kéré

Centre for Health and Social Welfare, photo courtesy of Francis Kéré

A poetic expression of light is consistent throughout Kéré’s works . Rays of sun filter into buildings, courtyards and intermediary spaces, overcoming harsh midday conditions to offer places of serenity or gathering. The concrete roof of Gando Primary School Library was poured around a grid of traditional clay pots, that once extracted, left openings allowing heat to escape while circular beams of natural light could linger and illuminate the interiors. A facade constructed of eucalyptus wood surrounds the elliptical building, creating flexible outdoor spaces that emit light vertically. Benga Riverside School (2018, Tete, Mozambique) features walls patterned with small recurring voids, allowing light and transparency to evoke feelings of trust from its students. The walls of Centre

for Health and Social Welfare (2014, Laongo, Burkina Faso) are adorned with a pattern of framed windows at varying heights to offer picturesque views of the landscape for everyone, from a standing doctor to a sitting visitor to a lying patient.

Kéré’s designs are laced with symbolism and his works outside of Africa are influenced by his upbringing and experiences in Gando. The West African tradition of communing under a sacred tree to exchange ideas, narrate stories, celebrate and assemble, is recurrent throughout . Sarbalé Ke at Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival (2019, California, United States) translates to “House of Celebration” in his native Bissa language, and references the shape of the hollowing baobab tree, revered in his homeland for its medicinal properties. The Serpentine Pavilion (2017, London, United Kingdom) also takes its central shape from the form of a tree and its disconnected yet curved walls are formed by triangular indigo modules, identifying with a color representing strength in his culture and more personally, a blue boubou garment worn by the architect as a child . The detached roof resonates with that of his buildings in Africa, but inside the pavilion, rainwater funnels into the center of the structure, highlighting water scarcity that is experienced worldwide. The Benin National Assembly (Porto-Novo, Republic of Benin), currently under construction and situated on a public park, is inspired by the palaver tree. While parliament convenes on the inside, citizens may also assemble under the vast shade at the base of the building.

Centre for Health and Social Welfare, photo courtesy of Francis Kéré

Centre for Health and Social Welfare, photo courtesy of Francis Kéré

The Citation continues, “In a world in crisis, amidst changing values and generations, he reminds us of what has been, and will undoubtably continue to be a cornerstone of architectural practice: a sense of community and narrative quality, which he himself is so able to recount with compassion and pride . In this he provides a narrative in which architecture can become a source of continued and lasting happiness and joy .”

Many of Kéré’s built works are located in Africa, in countries including the Republic of Benin, Burkino Faso, Mali, Togo, Kenya, Mozambique, Togo, and Sudan . Pavilions and installations and have been created in Denmark, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States . Significant works also include Xylem at Tippet Rise Art Centre (2019, Montana, United States), Léo Doctors’ Housing (2019, Léo, Burkina Faso), Lycée Schorge Secondary School (2016, Koudougou, Burkina Faso), the National Park of Mali (2010, Bamako, Mali) and Opera Village (Phase I, 2010, Laongo, Burkina Faso) .

Kéré established Kéré Foundation in 1998 to serve the inhabitants of Gando through the development of projects, partnerships and fundraising; and Kéré Architecture in 2005 in Berlin, Germany . Kéré is the 51st Laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize, and is a dual citizen of Burkina Faso and Germany .

About the Pritzker Architecture Prize

The Pritzker Architecture Prize was founded in 1979 by the late Jay A . Pritzker and his wife, Cindy . Its purpose is to honor annually a living architect or architects whose built work demonstrates a combination of those qualities of talent, vision and commitment, which has produced consistent and significant contributions to humanity and the built environment through the art of architecture.

Burkina Institute of Technology, photo courtesy of Francis Kéré

Burkina Institute of Technology, photo courtesy of Francis Kéré

Jury Citation

What is the role of architecture in contexts of extreme scarcity? What is the right approach to the practice when working against all odds? Should it be modest and risk succumbing to adverse circumstances? Or is modesty the only way to be pertinent and achieve results? Should it be ambitious in order to inspire change? Or does ambition run the risk of being out of place and of resulting in architecture of mere wishful thinking?

Francis Kéré has found brilliant, inspiring and game-changing ways to answer these questions over the last decades . His cultural sensitivity not only delivers social and environmental justice, but guides his entire process, in the awareness that it is the path towards the legitimacy of a building in a community . He knows, from within, that architecture is not about the object but the objective; not the product, but the process.

Francis Kéré’s entire body of work shows us the power of materiality rooted in place . His buildings, for and with communities, are directly of those communities – in their making, their materials, their programs and their unique characters. They are tied to the ground on which they sit and to the people who sit within them . They have presence without pretense and an impact shaped by grace .

Born in Burkina Faso to parents who insisted that their son be educated, Francis Kéré went on to the study of architecture in Berlin . Over and over, he has, in a sense returned to his roots . He has drawn from his European architectural formation and work, combining them with the traditions, needs and customs of his country . He was determined to bring resources in education from one of the leading Technical Universities in the world back to his native land and to have those resources elevate the indigenous know-how, culture and society of his region.

Léo Doctors’ Housing, photo courtesy of Francis Kéré

Léo Doctors’ Housing, photo courtesy of Francis Kéré

He has continuously pursued this task in ways at once highly respectful of place and tradition and yet transformational in what can be offered, as in the primary school in Gando which served as an example to so many even beyond the borders of Burkina Faso, and to which he later added a complex of teachers’ housing and a library. There, Kéré understood that an apparently simple goal, namely, to make it possible for children to attend school comfortably, had to be at the heart of his architectural project. Sustainability for a great majority of the world is not preventing undesirable energy loss so much as undesirable energy gains. For too many people in developing countries, the problem is extreme heat, rather than cold.

In response he developed an ad-hoc, highly performative and expressive architectural vocabulary: double roofs, thermal mass, wind towers, indirect lighting, cross ventilation and shade chambers (instead of conventional windows, doors and columns) have not only become his core strategies, but have actually acquired the status of built dignity. Since completing the school in his native village, Kéré has pursued the ethos and the method of working with local craft and skills to elevate not only the civic life of small villages, but soon also of national deliberations in legislative buildings . This is the case of his two projects underway for the Benin National Assembly, in advanced construction, and for the Burkina Faso National Assembly, temporarily halted by the current political situation in the country.

Lycée Schorge Secondary School, photo courtesy of Francis Kéré

Lycée Schorge Secondary School, photo courtesy of Francis Kéré

Francis Kéré’s work is, by its essence and its presence, fruit of its circumstances . In a world where architects are building projects in the most diverse contexts – not without controversies – Kéré contributes to the debate by incorporating local, national, regional and global dimensions in a very personal balance of grass roots experience, academic quality, low tech, high tech, and truly sophisticated multiculturalism . In the Serpentine pavilion, for example, he successfully translated into a universal visual language and in a particularly effective way, a long-forgotten essential symbol of primordial architecture worldwide: the tre .

He has developed a sensitive, bottom-up approach in its embrace of community participation. At the same time, he has no problem incorporating the best possible type of top-down process in his devotion to advanced architectural solutions. His simultaneously local and global perspective goes well beyond aesthetics and good intentions, allowing him to integrate the traditional with

the contemporary.

Francis Kéré’s work also reminds us of the necessary struggle to change unsustainable patterns of production and consumption, as we strive to provide adequate buildings and infrastructure for billions in need . He raises fundamental questions of the meaning of permanence and durability of construction in a context of constant technological changes and of use and re-use of structures.

At the same time his development of a contemporary humanism merges a deep respect for history, tradition, precision, written and unwritten rules.

Since the world began to pay attention to the remarkable work and life story of Francis Kéré, he has served as a singular beacon in architecture . He has shown us how architecture today can reflect and serve needs, including the aesthetic needs, of peoples throughout the world . He has shown us how locality becomes a universal possibility . In a world in crisis, amidst changing values and generations, he reminds us of what has been, and will undoubtably continue to be a cornerstone of architectural practice: a sense of community and narrative quality, which he himself is so able to recount with compassion and pride. In this he provides a narrative in which architecture can become a source of continued and lasting happiness and joy .

For the gifts he has created through his work, gifts that go beyond the realm of the architecture discipline, Francis Kéré is named the 2022 Pritzker Prize Laureate.

National Park of Mali, photo courtesy of Francis Kéré

National Park of Mali, photo courtesy of Francis Kéré

Jury Members

Alejandro Aravena (Chair)

Architect, Educator and 2016 Pritzker Laureate

Santiago, Chile

Barry Bergdoll

Architecture Historian, Educator, Curator and Author

New York, New York

Deborah Berke

Architect and Dean, Yale School of Architecture

New York, New York

Stephen Breyer

U.S. Supreme Court Justice

Washington, DC

André Aranha Corrêa do Lago

Architectural Critic, Curator and Brazilian Ambassador to India

Delhi, India

Kazuyo Sejima

Architect and 2010 Pritzker Laureate

Tokyo, Japan

Wang Shu

Architect, Educator and 2012 Pritzker Laureate

Hangzhou, China

BenedettaTagliabue

Architect and Educator

Barcelona, Spain

Manuela Lucá-Dazio (Executive Director)

Paris, France

National Park of Mali, photo courtesy of Iwan Baan

National Park of Mali, photo courtesy of Iwan Baan

Biography

Francis Kéré (b . Diébédo Francis Kéré, 1965) was born in Burkina Faso – one of the world’s least educated and most impoverished nations, a land void of clean drinking water, electricity and infrastructure, let alone architecture.

“I grew up in a community where there was no kindergarten, but where community was your family . Everyone took care of you and the entire village was your playground . My days were filled with securing food and water, but also simply being together, talking together, building houses together . I remember the room where my grandmother would sit and tell stories with a little light, while we would huddle close to each other and her voice inside the room enclosed us, summoning us to come closer and form a safe place . This was my first sense of architecture .”

Kéré was the oldest son of the village chief and the first in his community to attend school, only the city of Gando didn’t have a school, so he left his family at the age of seven . His small childhood classroom in Tenkodogo was constructed of cement blocks and lacked ventilation and light. Trapped in that extreme climate with over one hundred classmates for hours at a time, he vowed to one day make schools better.

“Good architecture in Burkina Faso is a classroom where you can sit, have light that is filtered, entering the way that you want to use it, across a blackboard or on a desk . How can we take away the heat coming from the sun, but use the light to our benefit? Creating climate conditions to give basic comfort allows for true teaching, learning and excitement .”

Gando Primary School, photo courtesy of Erik-Jan Owerkerk

Gando Primary School, photo courtesy of Erik-Jan Owerkerk

In 1985, he uprooted again, this time, much further from home, traveling to Berlin on a vocational carpentry scholarship, learning to make roofs and furniture by day, while attending secondary classes at night . He was awarded a scholarship to attend Technische Universität Berlin (Berlin, Germany) in 1995, graduating in 2004 with an advanced degree in architecture.

Although far from Burkina Faso, Kéré’s mind never strayed from his native homeland. He recognized the responsibility of his privilege, establishing the foundation “Schulbausteine für Gando e .V .”, translated to “school building blocks for Gando” and later renamed Kéré Foundation e .V ., in 1998 to fundraise and advocate for a child’s right to a comfortable classroom. His first building,

Gando Primary School (2001, Gando, Burkina Faso), was built by and for the people of Gando. Locals offered their input, labor and resources from conception to completion, crafting nearly every part of the school by hand, guided by the architect’s inventive forms of indigenous materials and modern engineering.

The success of Gando Primary School awarded him the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2004, and was the catalyst for establishing his practice, Kéré Architecture, in Berlin, Germany in 2005 . The realization of additional primary, secondary, postsecondary and medical facilities soon followed throughout Burkina Faso, Kenya, Mozambique and Uganda. Kéré’s built works in Africa have yielded exponential results, not only by providing academic education for children and medical treatment for the unwell, but by instilling occupational opportunities and abiding vocational skills for adults, therefore serving and stabilizing the future of entire communities.

Gando Primary School, photo courtesy of Erik-Jan Owerkerk

Gando Primary School, photo courtesy of Erik-Jan Owerkerk

With each trip back to Gando, Kéré has bestowed purposeful ideas, technical knowledge, environmental understanding and aesthetic solutions, but his service to humanity through cultural sensitivity, process of engagement and devotion proves as a constant example of generosity to the world . “I considered my work a private task, a duty to this community . But every person can take the time to go and investigate from things that are existing . We have to fight to create the quality that we need to improve people’s lives .”

His work has expanded beyond school buildings in African countries to include temporary and permanent structures in Denmark, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States . Two historic parliament buildings, the National Assembly of Burkina Faso (Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso) and Benin National Assembly (Porto-Novo, Republic of Benin), have been commissioned, with the latter currently under construction.

Additional awards include the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine’s Global Award for Sustainable Architecture (2009), BSI Swiss Architectural Award (2010); the Global Holcim Awards Gold (2012, Zurich, Switzerland), Schelling Architecture Award (2014); Arnold W Brunner Memorial Prize in Architecture from the American Academy of Arts & Letters (2017); and the Thomas Jefferson Foundation Medal in Architecture (2021).

The architect has been a visiting professor at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design (Massachusetts, United States), Yale School of Architecture (Connecticut, United States), and holds the inaugural Chair of Architectural Design and Participation professorship at the Technische Universität München (Munich, Germany) since 2017 . He is an Honorary Fellow of Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (2018) and the American Institute of Architects (2012) and a chartered member of the Royal Institute of British Architects (2009).

Kéré is a dual citizen of Burkina Faso and Germany and spends his time professionally and personally equally in both countries.

Xylem, photo courtesy of Iwan Baan

Xylem, photo courtesy of Iwan Baan

Xylem, photo courtesy of Francis Kéré

Xylem, photo courtesy of Francis Kéré

Xylem, photo courtesy of Iwan Baan

Xylem, photo courtesy of Iwan Baan

Fact Summary

BUILT WORKS

2021 Startup Lions Campus, Turkana County, Kenya

2020 Burkina Institute of Technology, Phase I, Koudougou, Burkina Faso

SKF-RTL Children Leaning Centre, Nyang’oma Kogelo, Kenya

2019 Xylem, Montana, United States

Sarbalé Ke, California, United States

Léo Doctors’ Housing, Léo, Burkina Faso

Gando Primary School Library, Gando, Burkina Faso

2018 Benga Riverside School, Tete, Mozambique

2017 Serpentine Pavilion, London, United Kingdom

2016 Lycée Schorge Secondary School, Koudougou, Burkina Faso

Noomdo Orphanage, Koudougou, Burkina Faso

2014 Surgical Clinic and Health Centre, Léo, Burkina Faso

Benga Riverside Residential Community, Phase I, Tete, Mozambique

Centre for Health and Social Welfare, Laongo, Burkina Faso

2011 Naaba Belem Goumma Secondary School, Phase I, Gando, Burkina Faso

2010 Opera Village, Phase I, Laongo, Burkina Faso

National Park of Mali, Bamako, Mali

Center for Earth Architecture, Mopti, Mali

2008 Gando Primary School Extension, Gando, Burkina Faso 2007 Dano Secondary School, Dano, Burkina Faso

2004 Gando Teachers’ Housing, Gando, Burkina Faso

2001 Gando Primary School, Gando, Burkina Faso

WORKS IN PROGRESS

Goethe-Institut, Dakar, Senegal

Speakers Corner, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso TUM Tower, Munich, Germany

Memorial Thomas Sankara, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso

Kamwokya Community Playground, Kampala, Uganda

Benga Riverside Residential Community, Phase II, Tete, Mozambique

Benin National Assembly, Porto-Novo, Republic of Benin

Burkina Institute of Technology, Phase II, Koudougou, Burkina Faso

Freie Waldorfschule Weilheim, Weilheim, Germany

Naaba Belem Goumma Secondary School, Phase II, Gando, Burkina Faso

Naume Children’s Foundation, Gulu, Uganda

Opera Village, Phase II, Laongo, Burkina Faso

TEMPORARY STRUCTURES AND INSTALLATIONS

2018–2019 Racism . The Invention of Human Races, Deutsches Hygiene-Museum, Dresden, Germany

2018 Tugunora, Therme Forum at Design Miami, Florida, United States

2017 Volksbühne Satellite Theatre, Tempelhof Airport, Berlin, Germany

2016 Colorscape, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, United States

Courtyard Village, Fuorisalone, Milan, Italy

2015 Louisiana Canopy, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark

Place for Gathering, Chicago Architecture Biennial, Illinois, United States

2014 Sensing Spaces Pavilion, Royal Academy of Arts, London, United Kingdom 2012 International Red Cross and Red Crescent Museum, Geneva, Switzerland

SOLO EXHIBITIONS

2021 Arbre à Palabres, Aedes Galerie, Berlin, Germany

2016– Francis Kéré: Radically Social, Pinakothek der Moderne, Munich, Germany 2017

2016 The Architecture of Francis Kéré: Building for Community, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, United States

GROUP EXHIBITIONS

2021 Momentum of Light, Zumtobel Light Forum, Dornbirn, Austria

Kunstmuseum, Olten, Switzerland

Summer Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts, London, United Kingdom

2019 What is Radical Today, Royal Academy of Arts, London, United Kingdom

Social Design, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg, Germany

2018–2019 Francis Kéré. Primary Elements, ICO Madrid, Madrid, Spain

2016 constellation.s: habiter le monde, Arc en Rêve Centre d’Architecture, Bordeaux, France

Reporting from the Front, La Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy

2015– 2016 The State of the Art of Architecture, Chicago Architectural Biennial, Illinois, United States

2015 Africa: Architecture and Identity. Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark

2014 Sensing Spaces. Architecture Reimagined, Royal Academy of Arts, London, United Kingdom

Fundamentals, La Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy

Ré-enchanter le Monde, Cité de l‘Architecture et du Patrimoine, Paris, France

2011 MACHEN! Aedes, Berlin, Germany

2010–2011 Small Scale, Big Change: New Architectures of Social Engagement, Museum of Modern Art,

New York, United States

2010 Rwanda Pavilion, La Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy

SELECTED AWARDS

2021 Thomas Jefferson Foundation Medal in Architecture, United States

2017 Prince Claus Laureate Award, Prince Claus Fund, The Netherlands

2017 Arnold W . Brunner Memorial Prize, American Academy of Arts & Letters, United States

2015 Kenneth Hudson Award for European Museum of the Year, for the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Museum Permanent Exhibition, United Kingdom

2014 Schelling Architecture Award, Schelling Architecture Foundation, Germany

2012 Global Holcim Awards, Holcim Foundation, Switzerland

2011 Gold Holcim Award for Middle East Africa, Holcim Foundation, Switzerland

2011 Marcus Prize for Architecture, United States

2010 BSI Swiss Architectural Award, Switzerland

2009 Global Award for Sustainable Architecture, Cité de l’Architecture & du Patrimoine, France

2006 Chevalier de L’Ordre National of Burkina Faso for Gando Primary School Extension

2004 Aga Khan Award for Architecture, Switzerland for Gando Primary School

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

2021 Baan, Iwan, and Francis Kéré . Francis Kéré & Iwan Baan: Momentum of Light . Lars Müller

Publishers, 2021 .

2021 Kéré Architecture: Abre à Palabres, Aedes, 2021 .

2019 Kéré Architecture, A .mag, 17, 2019 .

2018 Francis Kéré - Primary Elements . Avisa, 2018 .

2018 Francis Kéré: Serpentine Pavilion 2017, Walther König, Köln, 2018 .

2018 ONE Kéré Architecture, Lycée Francis Kéré Schorge Secondary School, A .mag, 04, 2018 .

2017 Francis Kéré: Practical Aesthetics, Av Monographs, Avisa, 201, 2017 .

2010 Small Scale, Big Change: New Architectures of Social Engagement, The Museum of Modern Art, 2010 .

2009 Domus, 927, 2009 .

Ceremony Venue

The Marshall Building, designed by Grafton Architects, led by 2020 Laureates, Yvonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara, is the largest ever academic building at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) . Completed in 2021, it houses a multiplicity of different departments and functions in an uplifting and expressive building. The Great Hall is an open and permeable convening space, which links the hinterland of LSE’s university quarter with London’s largest public square – Lincoln’s Inn Fields . The exterior of the building is composed of Portland stone and concrete, featuring vertical screens and fins to balance light and shade, while the interior includes tree-like columns that branch into diagonal beams, connecting the sloping terrazzo floor to the vaulted ceiling . Predicated on enhancing the student and staff experience, the building accommodates sports and arts facilities, lecture theaters and seminar rooms, faculty accommodation for the departments of Accounting, Finance and Management and research space for Systemic Risk, Financial Markets Group and the Paul Marshall Institute for Philanthropy and Social Entrepreneurship.

About the Medal

The bronze medallion awarded to each Laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize is based on designs of Louis Sullivan, famed Chicago architect generally acknowledged as the father of the skyscraper . On one side is the name of the prize. On the reverse, three words are inscribed, “firmness, commodity and delight .” These are the three conditions referred to by Henry Wotton in his 1624 treatise, The Elements of Architecture, which was a translation of thoughts originally set down nearly 2,000 years ago by Marcus Vitruvius in his Ten Books on Architecture, dedicated to the Roman Emperor Augustus. Wotton, who did the translation when he was England’s first ambassador to Venice, used the complete quote as: “The end is to build well. Well-building hath three conditions: commodity, firmness and delight .”

History of the Prize

The Pritzker Architecture Prize was established by The Hyatt Foundation in 1979 to annually honor a living architect whose built work demonstrates a combination of those qualities of talent, vision and commitment, which has produced consistent and significant contributions to humanity and the built environment through the art of architecture . It has often been described as “architecture’s most prestigious award” or as “the Nobel of architecture .”

The prize takes its name from the Pritzker family, whose international business interests, which include the Hyatt Hotels, are headquartered in Chicago . They have long been known for their support of educational, social welfare, scientific, medical and cultural activities . Jay A . Pritzker, who founded the prize with his wife, Cindy, died on January 23, 1999 . His eldest son, Thomas J. Pritzker, has become chairman of The Hyatt Foundation. In 2004, Chicago celebrated the opening of Millennium Park, in which a music pavilion designed by Pritzker Laureate Frank Gehry was dedicated and named for the founder of the prize . It was in the Jay Pritzker Pavilion that the 2005 awarding ceremony took place.

Tom Pritzker explains, “As native Chicagoans, it’s not surprising that we are keenly aware of architecture, living in the birthplace of the skyscraper, a city filled with buildings designed by architectural legends such as Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe and many others .”

He continues, “In 1967, our company acquired an unfinished building which was to become the Hyatt Regency Atlanta. Its soaring atrium was wildly successful and became the signature piece of our hotels around the world . It was immediately apparent that this design had a pronounced effect on the mood of our guests and attitude of our employees . While the architecture of Chicago made us cognizant of the art of architecture, our work with designing and building hotels made us aware of the impact architecture could have on human behavior .”

And he elaborates further, “So in 1978, when the family was approached with the idea of honoring living architects, we were responsive . Mom and Dad (Cindy and the late Jay A . Pritzker) believed that a meaningful prize would encourage and stimulate not only a greater public awareness of buildings, but also would inspire greater creativity within the architectural profession .” He went on to add that he is extremely proud to carry on that effort on behalf of his family.

Many of the procedures and rewards of the Pritzker Prize are modeled after the Nobel Prize. Laureates of the Pritzker Architecture Prize receive a $100,000 grant, a formal citation certificate, and since 1987, a bronze medal. Prior to that year, a limited edition Henry Moore sculpture was presented to each Laureate.

Nominations are accepted from all nations; from government officials, writers, critics, academicians, fellow architects, architectural societies or industrialists, virtually anyone who might have an interest in advancing great architecture. The prize is awarded irrespective of nationality, race, creed, gender or ideology.

The nominating procedure is continuous from year to year, closing each November . Nominations received after the closing are automatically considered in the following calendar year . The final selection is made by an international jury through undisclosed deliberations and voting.