The global construction industry, due to its vast scale, complexity, and essential role in national economies, is grappling with the challenge of shifting away from the traditional, resource- and labor-intensive methods toward more sustainable practices. Sustainability standards, such as building and material certifications, are now common in most public projects and are increasingly shaping private sector investments as well. Today, it’s standard practice for designers and investors to consider the origin, production, and full life cycle of the materials they use.

Yet a more transformative shift is gaining momentum, driven by designers who embrace the increasingly familiar idea that “the greenest building is one that is already built.” This philosophy, centered on reimagining and reusing existing structures, is being adopted by leading design firms across the U.S. One of its strongest advocates is architect and urban designer Zuzanna Jarzynska, whose work spans both Europe and North America.

Jarzynska holds a degree from the Faculty of Architecture at Warsaw University of Technology and a post-professional degree from Columbia University. Her past work with BBGK Architects—a Mies van der Rohe Award finalist for its renovation and adaptation of the Katyn Museum—focused on buildings deeply embedded in community memory and the often-overlooked history of Warsaw, Poland. Now an Associate at Beyer Blinder Belle Architects and Planners, she collaborates with cultural and academic institutions to revitalize and restore historic buildings (many over a century old) ensuring they can thrive for another hundred years while adapting to new missions, evolving uses, and contemporary programs.

Why concentrate on existing buildings?

There are so many reasons, but it really comes down to this: buildings are assets. In some governance contexts, they are even more valuable than the land they stand on. The simple idea is to take full advantage of the physical resources, design and construction effort already invested, and to build upon that foundation. The mission to reuse what already exists, instead of spending time and resources demolishing and replacing it, goes beyond common sense or frugality.

In our built surroundings, existing structures carry memories, traditions, and traces of bygone eras. In Western conservation philosophy, these are considered irreplaceable, immeasurable values worth preserving. The American cultural and educational institutions I’m currently working with understand this deeply and not just because of the strict regulations imposed by local Landmarks Preservation Commissions. These buildings serve as repositories of institutional memory, acting as the backdrop to significant moments in their histories. Nothing can replace the symbolic weight and architectural presence of a great American museum, school, or century-old library hall.

But for these buildings to remain relevant and not become burdensome to evolving institutions, their new missions, or future goals, they must be adapted and revitalized. That’s where my role begins. Alongside historians and structural and systems engineers, we envision how a building should function over the next 30 to 50 years. Our work doesn’t stop there, though; we look even further ahead, anticipating what comes next by keeping our designs flexible and open to future improvements, and accounting for technological advances and evolving building materials. A strong understanding of history helps us learn from the mistakes of our predecessors, and to reveal the inherent value that often lies hidden beneath layers of past renovations.

Zuzanna and her teams on design sites. Review of ductwork collisions with historic fabric (left), Rooftop conservation survey (right).

Zuzanna and her teams on design sites. Review of ductwork collisions with historic fabric (left), Rooftop conservation survey (right).

Could you share some examples of design or strategies you implemented to improve efficiency and resiliency of existing buildings?

To a layperson, much of my work might seem highly technical. The strategies we implement are data-driven and specifically tailored to each building’s function and historic structure.

A single intervention can be deceptively simple, like the interior installation of storm-resilient aluminum and glass barriers, which I worked on last year for one of Brooklyn’s largest museum institutions, originally constructed in the 1910s. That particular project involved exhibiting extremely light- and temperature-sensitive objects in galleries currently at risk due to beautiful but aging steel windows, now over a century old. These windows, while architecturally significant, were deteriorating and prohibitively expensive to replace. So, we designed a secondary protective envelope from the inside, allowing us to meet strict environmental requirements without altering the historic fabric of the façade.

We developed a cohesive interior design that embraced the existing terrazzo floors, mosaics, millwork, coves, sills, and casings, treating every original element as a design asset. By building on this historical material palette, we achieved stringent climate-control goals required by art conservators, while also supporting the institution’s broader mission: improving resiliency, reducing maintenance costs, and preventing elemental deterioration.

Our process always begins with extensive historical research that includes reviewing archival documentation from the institution or local preservation foundations. We follow with visual surveys, material sampling, and thermographic imaging. From there, we model thermal, daylight, and humidity scenarios to inform design decisions. I aim to identify what still works in a building, preserve what has proven resilient, and then build upon that foundation to support the next 100 years of its life.

Another adaptation and preservation story I’m especially excited about is the “extension from within” of the main classroom and assembly building at a prominent private secondary school in New Hampshire. We partnered with the school on their ongoing campus-wide transition to geothermal energy, while tackling what many saw as impossible: expanding their historic auditorium— schools’s symbolic heart and location of its legacy student assemblies—from 800 to 1,200 seats.

The challenge? The hall is situated at the center of a symmetrical Beaux-Arts-style building with a nearly fixed exterior footprint and surrounded by 45 classrooms on two floors, none of which could be reduced in size. Through precise spatial reorganization and a minimally expanded footprint, we created space not just for a larger hall, but also for a new prefabrication lab, informal gathering spaces, and a state-of-the-art auditorium with upgraded acoustics and AV capabilities to support a wider range of performances and events.

Construction is set to begin in Summer 2025, and we’re thrilled to see how the school's remarkable student body will bring new life to the reimagined space.

The New Emilia Pavilion. Existing roof and prefabricated structure stored for reuse.

The New Emilia Pavilion. Existing roof and prefabricated structure stored for reuse.

These are the stories of beloved halls with continued institutional ownership and programming. But what happens when an existing building becomes an unwanted burden to its owner?

Sometimes, you have to flip the script, even if that means relocating a building so it can be fully appreciated.

I often anticipate confusion, even agitation, from Western preservation theorists when I talk about one of my most debated projects: the 2018 reconstruction of the New Emilia Pavilion in central Warsaw. Originally a wonderfully simple and elegant modernist structure housing a modern furniture showroom, it had recently been adapted as the new hip location of the Warsaw Museum of Contemporary Art. Most Varsovians followed closely the heated public debate that erupted when ownership of the site was transferred to a developer planning to build a new skyscraper in its place. The public outrage was understandable: less than a decade earlier, another iconic modernist landmark, SuperSam (a food department store) on Lubelski Union Square, had suffered the same fate.

At that point, the then–Warsaw Municipal Conservator approached our team at BBGK Architects with a bold proposal: dismantle the pavilion and reconstruct it on public land, where it could remain accessible for generations to come. That’s what we did.

We proposed a meticulous dismantling and reuse of over 60% of the original reinforced concrete roof and salvaged all the interior finishes, including the prefabricated terrazzo staircases and thousands of square feet of original terrazzo flooring. Its new location, aligned with the northern axis of the Palace of Culture in Warsaw (funnily enough, just 250m away from the original location), gives the light-filled, glass-walled pavilion the four-sided exposure it always deserved—now beautifully framed by a park. Reimagined through a public–private investment model, the project also includes an expanded basement with a 600-person exhibition hall. The upper levels are being transformed into open public spaces: a café, calisthenics zone, quiet rest areas, and even a small arboretum.

Currently, the City of Warsaw is focused on completing several major civic projects on the east side of the Palace of Culture. Among them, the new Museum of Contemporary Art (designed by American studio Thomas Phifer & Partners), a new theatre, and the redevelopment of Warsaw Central Square. But we fully expect attention and funding to soon shift northward. When it does, the New Emilia Pavilion, already deeply loved by Varsovians, will be in place to complete the evolving composition of what has always been the most important public space in the city.

My goal is not to argue that every heritage structure on a contested site should simply "move over." But I do believe that when public officials, creative designers, and committed entrepreneurs work together, there’s real potential for bold, innovative solutions, ones that inspire future stakeholders and provoke essential public conversations.

Warsaw Social District. Overview of historic structures.

Warsaw Social District. Overview of historic structures.

How does this translate to your similarly extensive work in the urban scale?

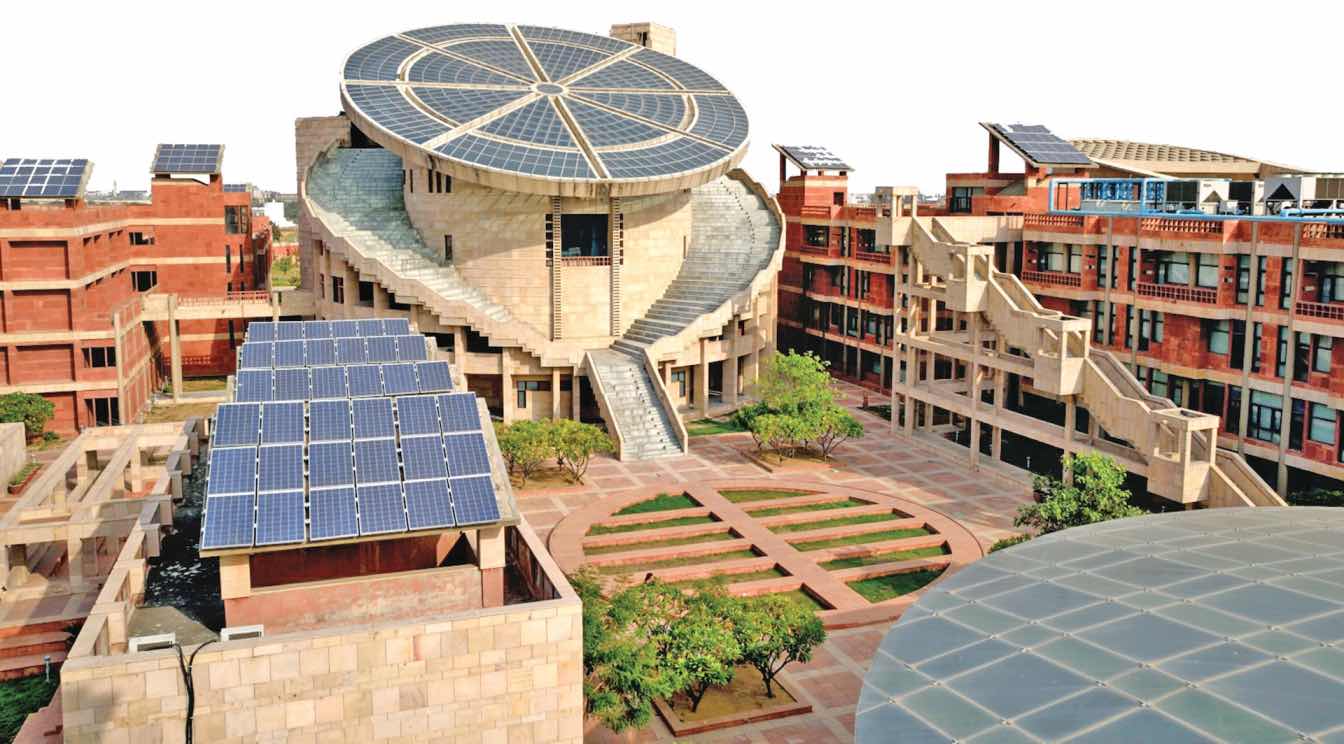

My interest in the urban scale stems from the simple fact that urban design always takes place within a complex, pre-existing context: a palimpsest that must be navigated with the mindset of a researcher, analyst, and innovator at the same time. Urban planning rarely begins with a blank slate, especially in North America and Europe; it’s rare to be handed a completely vacant parcel of land with no constraints. More often, we work with layered histories, physical remnants, and complicated ownership structures. During my year-long work on the Warsaw Social District—a highly successful and widely discussed concept for a new model housing development on a former industrial site—our design was deeply informed by context. The relationship with neighboring communities and the presence of beautiful historic brick structures helped establish our design priorities, create a sense of genius loci, and serve as compositional anchors within the master plan.

It all began in early 2017, when BBGK Architects, my studio at the time, was approached by the Warsaw Bureau of Architecture and Urban Planning. The city’s Chief Architect brought us a plot in Ulrychów—a former manufacturing site once used for producing the socialist-era concrete prefabricated housing that dominates much of postwar Warsaw. As I led a detailed site survey, I came across several derelict brick buildings. Rather than clearing the site, I began to consider what value these remnants could offer.

After assessing their structural stability and material quality, my team and I proposed reusing two of the 1950s brick buildings by transforming one into a public nursery and kindergarten, the other into a sports hall. But the most exciting idea came from an unexpected source: two abandoned cement silos. We imagined, and ultimately proposed, retrofitting them into a space that would house the largest indoor climbing boulders in Warsaw.

The mid-2010s marked a key moment for grey zone restoration across both Europe and the U.S. It was also the period when the term Productive City gained real traction. In 2017, Essen, Germany was named a European Green Capital for its remarkable transformation of a former industrial zone into the now-iconic Krupp Park. That recognition validated what many of us already believed: the sustainable cities of the future will be built on these once-feared, toxic, forgotten sites. When restored and remediated, these places hold enormous value - not just because of their favorable locations, but also for their historical and symbolic significance. Importantly, they embody the self-explanatory philosophy, difficult to argue with: one that values working intelligently with what already exists.

Zuzanna taking a 3d scan of an existing historic site.

Zuzanna taking a 3d scan of an existing historic site.

You’ve worked in both European and North American contexts. How has that influenced your design philosophy?

Starting my career in Europe deeply shaped my design instincts and priorities. European cities tend to be denser and more spatially efficient, which naturally leads to humbler proposals and more restrained, contextual interventions. You're often working with limited space, long histories, and tight urban fabrics that require subtlety and precision. In contrast, American cities tend to undergo transformations on a much larger and often more dramatic scale—driven by extreme natural events, economic shifts, or sociopolitical changes. Think of New York’s shipyards turning into expansive recreational waterfronts, Detroit’s depopulation and reinvention, or New Orleans’ battle with rising waters. American urbanism taught me that bold, even radical ideas aren’t just welcome - they’re often necessary. And they can be transformative.

When it comes to historic sites and adaptive reuse, I’ve noticed a striking difference in public perception. In the U.S., both professionals and everyday residents often take greater pride in their architectural heritage than their European counterparts. There’s a deeper emotional attachment, and a stronger sense of ownership over historic buildings, even relatively young ones. That fills me with hope.

Paired with what many consider a stereotypically American sense of resourcefulness and ingenuity, this cultural value has already sparked exciting developments in the past (the invention of a studio apartment in New York City!) and continues to do so today with the growing momentum behind office-to-residential conversions. It's proof that big ideas, when rooted in local pride and supported by smart policy, can become powerful tools for resilience and sustainability. I truly believe that these bold, adaptive strategies can serve as models for other nations as we face our shared challenges on the path toward a more sustainable future.