Details of rare 19th century photographs available online for the first time.

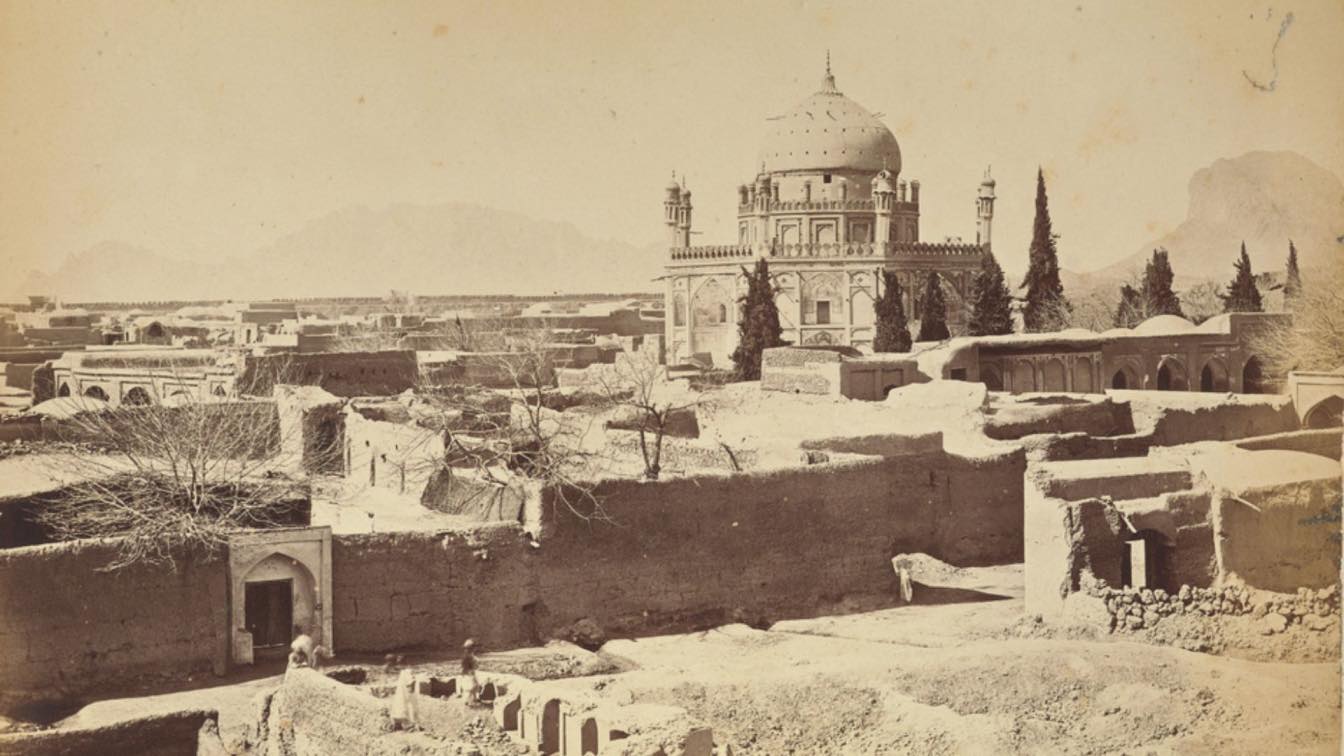

LOS ANGELES – Qandahar, Afghanistan, has stood at the center of cultural convergence and conflict for over two millennia. In 1881, toward the end of the Second Anglo-Afghan War, a British military doctor took among the earliest photographs of the city. Over 140 years later, the collection of what is known as the Qandahar Album can be explored online for the first time through a new Getty website.

At the Crossroads: Qandahar in Images and Empires, a new digital experience from the Getty Research Institute (GRI), includes dozens of the album’s pictures, which feature important heritage sites, the architecture of the city, and its inhabitants, as well as explanatory text in English, Dari, and Pashto.

Plate 1. No. 49. Artillery Square Showing the Main Bastion of the Citadel, 1881, Dr. Benjamin Simpson. Albumen print, 36 x 45 cm. Getty Research Institute, 2013.R.5

Situated at the intersection of ancient trade routes and surrounded by powerful Asian empires, it’s not surprising that walls nearly 30 feet thick and 30 feet high once framed Qandahar. Dr. Benjamin Simpson was a member of the British-Indian forces that controlled the city after defeating Ayub Khan, the governor of Herat, who attempted to rid Afghanistan of foreign intervention. Simpson’s intention was to document the region, key sites, and important players in the conflict.

“These photographs reveal the intrusions of the British occupation of Qandahar and speak to the resilience of a city and people caught between preserving their traditions and way of life and the inextricable forces of colonization and globalization,” said Aparna Kumar, lecturer in art and visual cultures of the Global South at University College London, in her essay about the photographs. “The album offers a crucial glimpse into the region’s past and endeavors to inspire further study on the history and culture of Afghanistan.”

Plate 9. No. 1. Tomb of Ahmad Shah, from the Southwest Bastion of the Citadel, 1881, Dr. Benjamin Simpson. Albumen print, 36 x 45 cm. Getty Research Institute, 2013.R.5

Simpson photographed Qandahar against the backdrop of several key moments during the war. His images memorialize key sites of conflict, including the village of Deh-i-Khoja, the Baba Wali Pass, and Karez Hill. But the photographs served other purposes as well—for surveillance, military strategy, and as propaganda for the British at home, who could be simultaneously dazzled by the region’s beauty and supportive of its occupation.

“Simpson was no amateur photographer—his passion and knowledge of photographic chemistry may explain why he chose to transport hundreds of pounds of equipment to Qandahar when he was stationed there,” said Frances Terpak, senior curator at the Getty Research Institute. “He had a point of view when he created the album and wanted to tell a visual story of the conflict in a way that a British veteran might recount it, no matter how one-sided the recollection.”

Plate 23. No. 36. Camels Coming Out of Bardurani Gate, 1881, Dr. Benjamin Simpson. Albumen print, 36 x 45 cm. Getty Research Institute, 2013.R.5

The spectacular architecture and urban design of Qandahar are present in nearly every photograph in the album. Founded by Ahmad Shah Durrani (r. 1747–72) in 1761, Qandahar was laid out like other contemporary urban centers in the early modern Persianate world, with neighborhoods organized by their inhabitants’ ethnicities, tribal identifications, and occupations.

At the city’s bustling bazaars, Herati merchants sold Iranian carpets and silks, nomads bartered hides and metalwork, and Hindus from Sindh/Shikarpur offered banking services. Indicative of the city’s importance as a commercial axis, its monumental gates were named after and faced the cities of Herat, Kabul, and Shikarpur, which formed the next link in a series of routes, radiating out and back, where goods and ideas abundantly flowed.

Plate 29. No. 34. Group of Timuris, 1881, Dr. Benjamin Simpson. Albumen print, 36 x 45 cm. Getty Research Institute, 2013.R.5

“The southern region of Afghanistan—often depicted in modern cultural visual products and writings as dusty desert-like society in need of development—has several layers of rich urban and cultural histories that go back millennia,” says Dr. Jawan Shir Rasikh, an independent scholar specializing in second millennium South and Central Asia with a focus on Afghanistan. “Simpson’s images in the Qandahar Album provide a valuable opportunity to get a concrete visual sense about 19th-century social and spatial landscapes of one of the region’s main urban centers.”

Plate 27. No. 29. Group of Hazaras, 1881, Dr. Benjamin Simpson. Albumen print, 36 x 45 cm. Getty Research Institute, 2013.R.5

Simpson also managed to photograph local ethnic groups, including Hazaras, Parsiwans, and Timuris. While not a full documentation of the city’s diversity, since 15,000 of its residents had been expunged by British troops, these are some of the few known photographs of these communities from the 19th century.

“Although most of Afghanistan’s historical heritage was destroyed or disappeared during the recent decades, the Qandahar Album not only gives Afghans a sense of continuity about their history but also fills the gap in understanding one of the most crucial periods of Afghanistan’s emergence as a nation-state,” says Dr. Omar Sharifi, country director of the American Institute of Afghanistan Studies.

Plate 24. No. 55. Afghan Horse Dealers, 1881, Dr. Benjamin Simpson. Albumen print, 36 x 45 cm. Getty Research Institute, 2013.R.5

The political events in Afghanistan in 2021 affected plans to display reproductions of the Kandahar Album there. The GRI, in partnership with the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, was planning a series of exhibitions across the country, but its instability forced them to pivot to an online format. However, this approach also created an opportunity for a broader international audience.

“While we hope to eventually exhibit these important images in Afghanistan, we’re delighted that this website will enable visitors access globally and in multiple languages,” says Ajmal Maiwandi, chief executive officer at Aga Khan Cultural Services, Afghanistan. “There are countless people in Afghanistan and within the Afghan diaspora who value these vignettes of history, and we are pleased to share this album with them in remembrance of their past.”

Plate 31. No. 74. Col. St. Johns’s Residence in the City, 1881, Dr. Benjamin Simpson. Albumen print, 36 x 45 cm. Getty Research Institute, 2013.R.5

Plate 8. No. 71. Kandahār from Hazratiji’s Shrine, 1881, Dr. Benjamin Simpson. Albumen print, 36 x 45 cm. Getty Research Institute, 2013.R.5

Plate 13. No. 41. Chilzina or the Forty Steps, 1881, Dr. Benjamin Simpson. Albumen print, 36 x 45 cm. Getty Research Institute, 2013.R.5

Plate 30. No. 11. Tombs of Hazratji and Sher Ali’s Father, 1881, Dr. Benjamin Simpson. Albumen print, 36 x 45 cm. Getty Research Institute, 2013.R.5

Plate 15. No. 46. Courtyard of Wali Sher Ali’s Zenana, 1881, Dr. Benjamin Simpson. Albumen print, 36 x 45 cm. Getty Research Institute, 2013.R.5

Plate 7. No. 60. The Base Camp Hospital Square and Cantonments, 1881, Dr. Benjamin Simpson. Albumen print, 36 x 45 cm. Getty Research Institute, 2013.R.5

Getty is a leading global arts organization committed to the exhibition, conservation, and understanding of the world’s artistic and cultural heritage. Working collaboratively with partners around the globe, the Getty Foundation, Getty Conservation Institute, Getty Museum and Getty Research Institute are all dedicated to the greater understanding of the relationships between the world’s many cultures. The Los Angeles-based J. Paul Getty Trust and Getty programs share art, knowledge, and resources online at Getty.edu and welcome the public for free at the Getty Center and the Getty Villa.

The Getty Research Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. It serves education in the broadest sense by increasing knowledge and understanding about art and its history through advanced research. The Research Institute provides intellectual leadership through its research, exhibition, and publication programs and provides service to a wide range of scholars worldwide through residencies, fellowships, online resources, and a Research Library. The Research Library—housed in the 201,000-square-foot Research Institute building designed by Richard Meier—is one of the largest art and architecture libraries in the world. The general library collections (secondary sources) include almost 900,000 volumes of books, periodicals, and auction catalogues encompassing the history of Western art and related fields in the humanities. The Research Library’s special collections include rare books, artists’ journals, sketchbooks, architectural drawings and models, photographs, and archival materials.